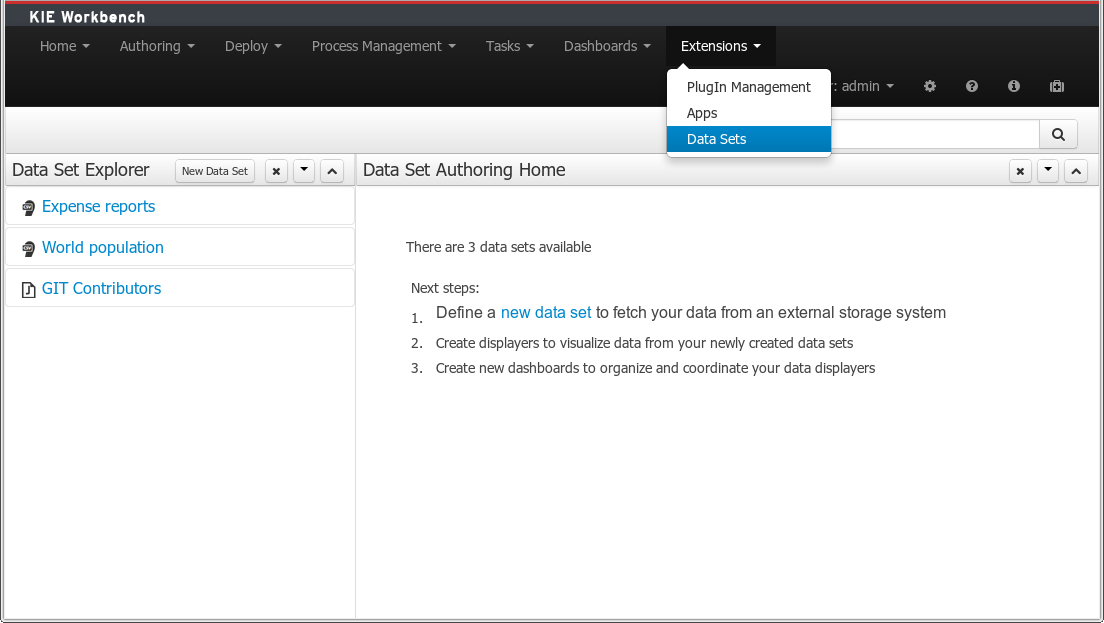

Welcome

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction

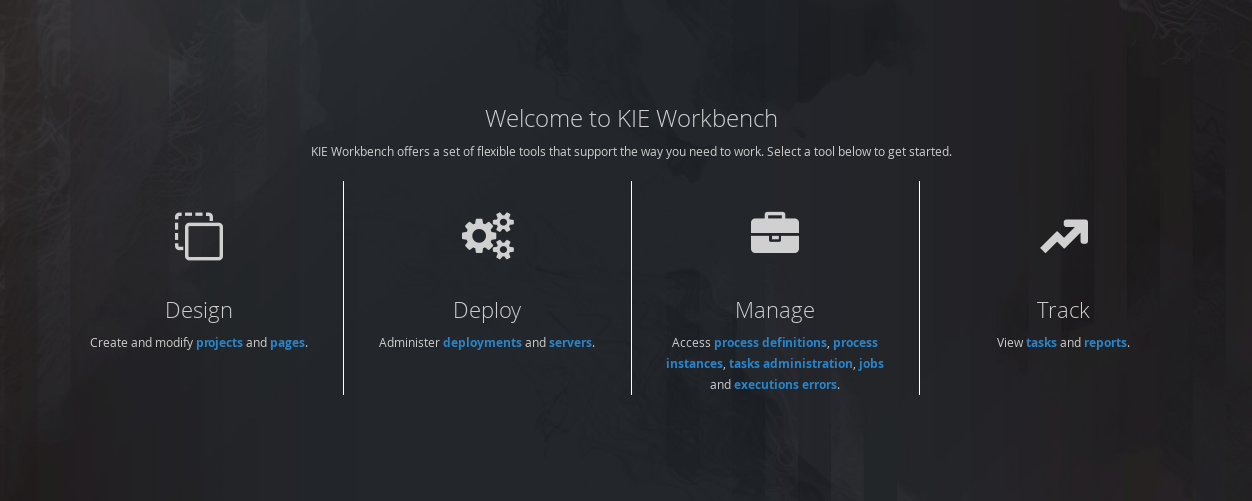

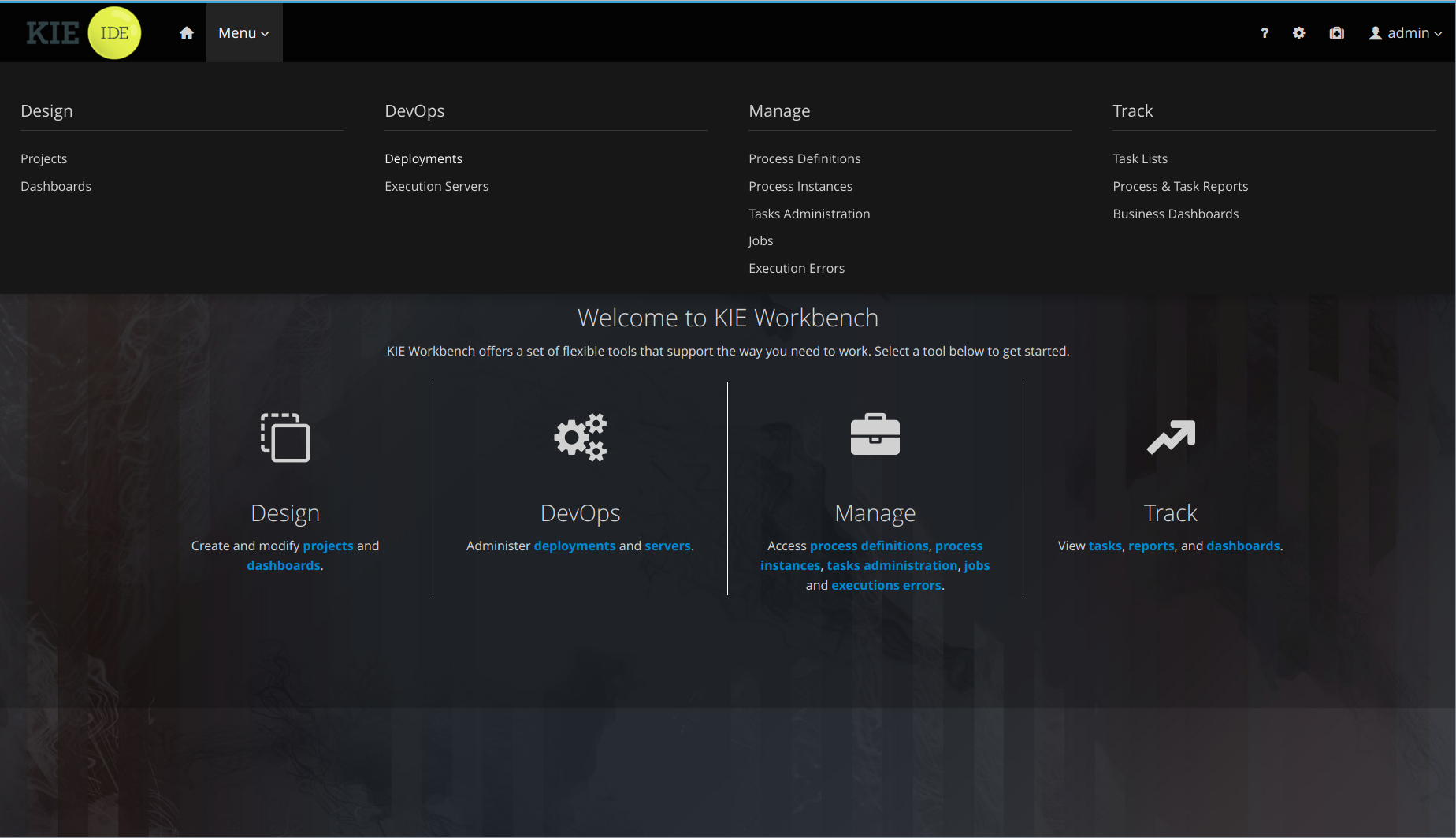

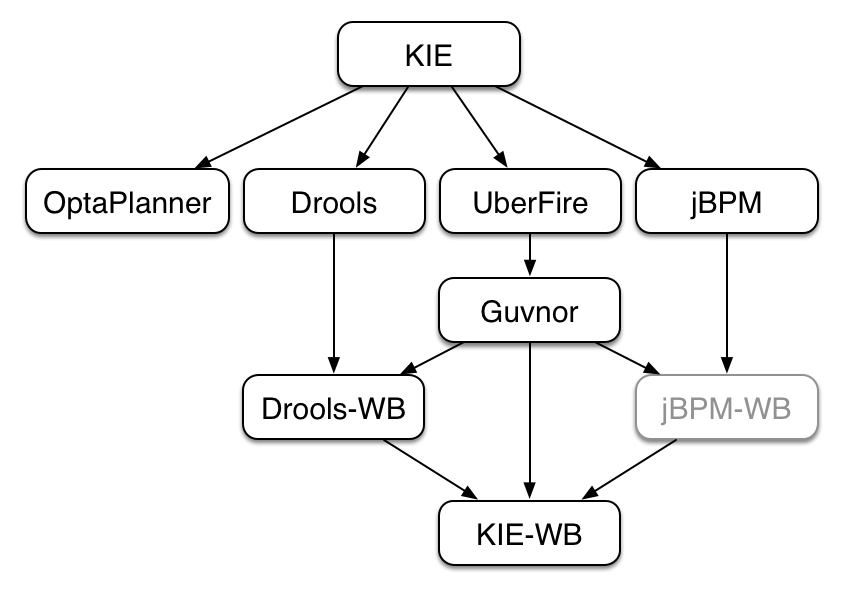

KIE (Knowledge Is Everything) is an umbrella project introduced to bring our related technologies together under one roof. It also acts as the core shared between our projects.

KIE contains the following different but related projects offering a complete portfolio of solutions for business automation and management:

-

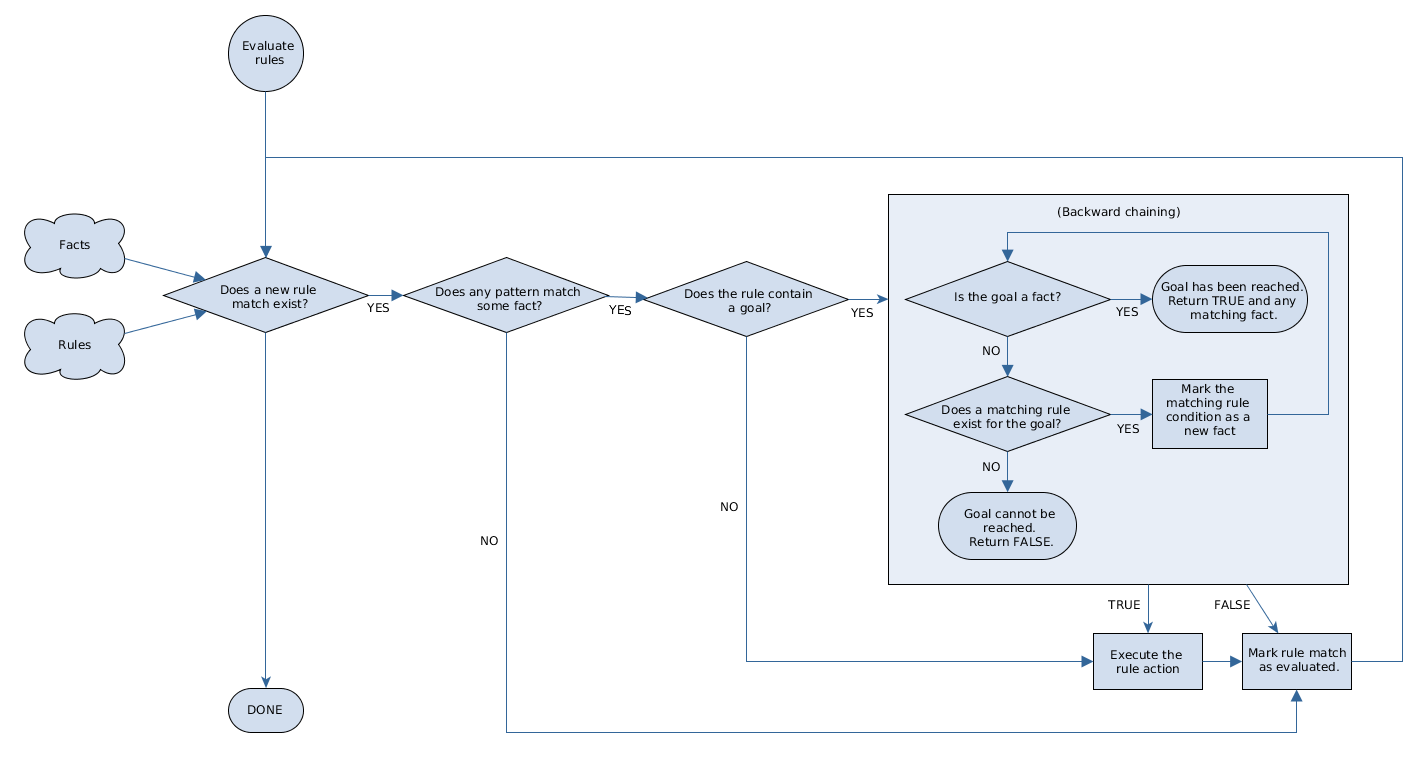

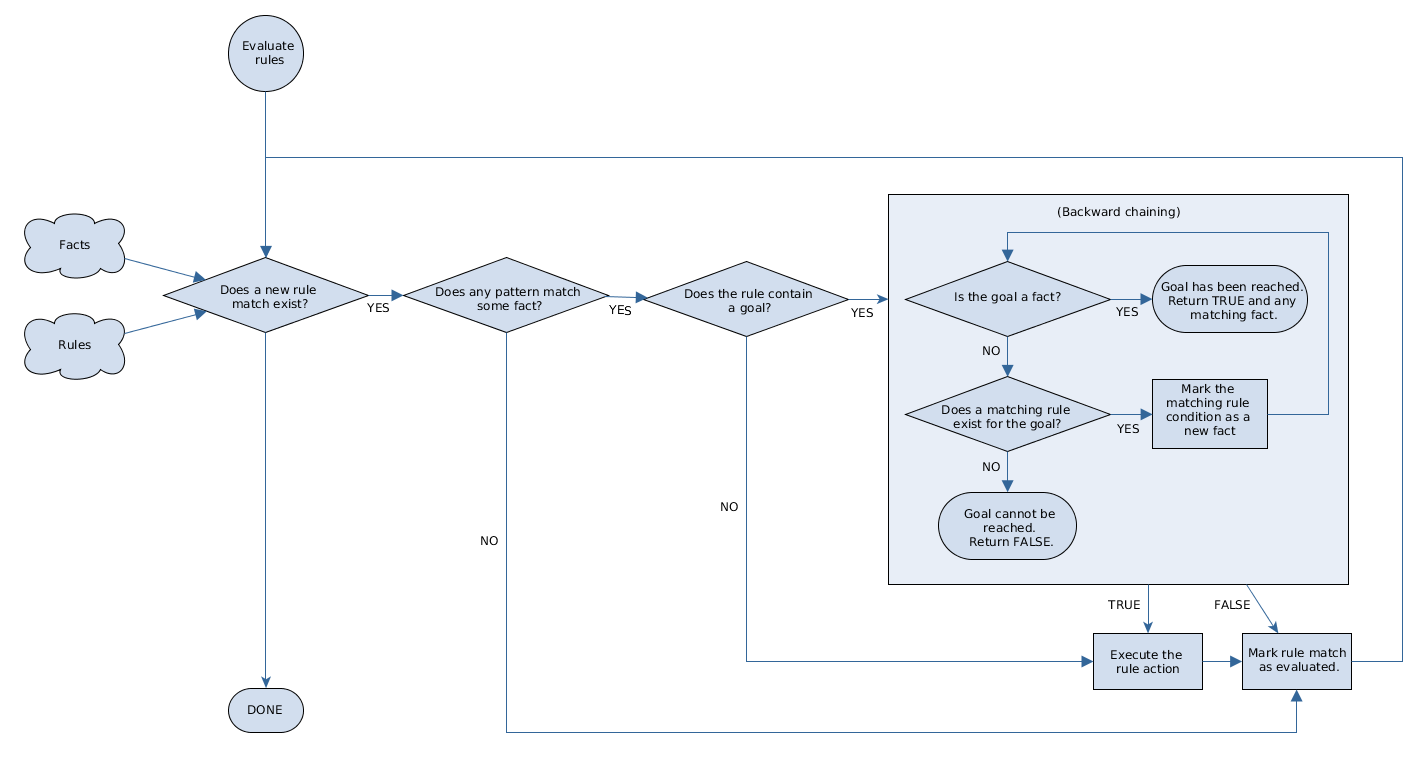

Drools is a business-rule management system with a forward-chaining and backward-chaining inference-based rules engine, allowing fast and reliable evaluation of business rules and complex event processing. A rules engine is also a fundamental building block to create an expert system which, in artificial intelligence, is a computer system that emulates the decision-making ability of a human expert.

-

jBPM is a flexible Business Process Management suite allowing you to model your business goals by describing the steps that need to be executed to achieve those goals.

-

OptaPlanner is a constraint solver that optimizes use cases such as employee rostering, vehicle routing, task assignment and cloud optimization.

-

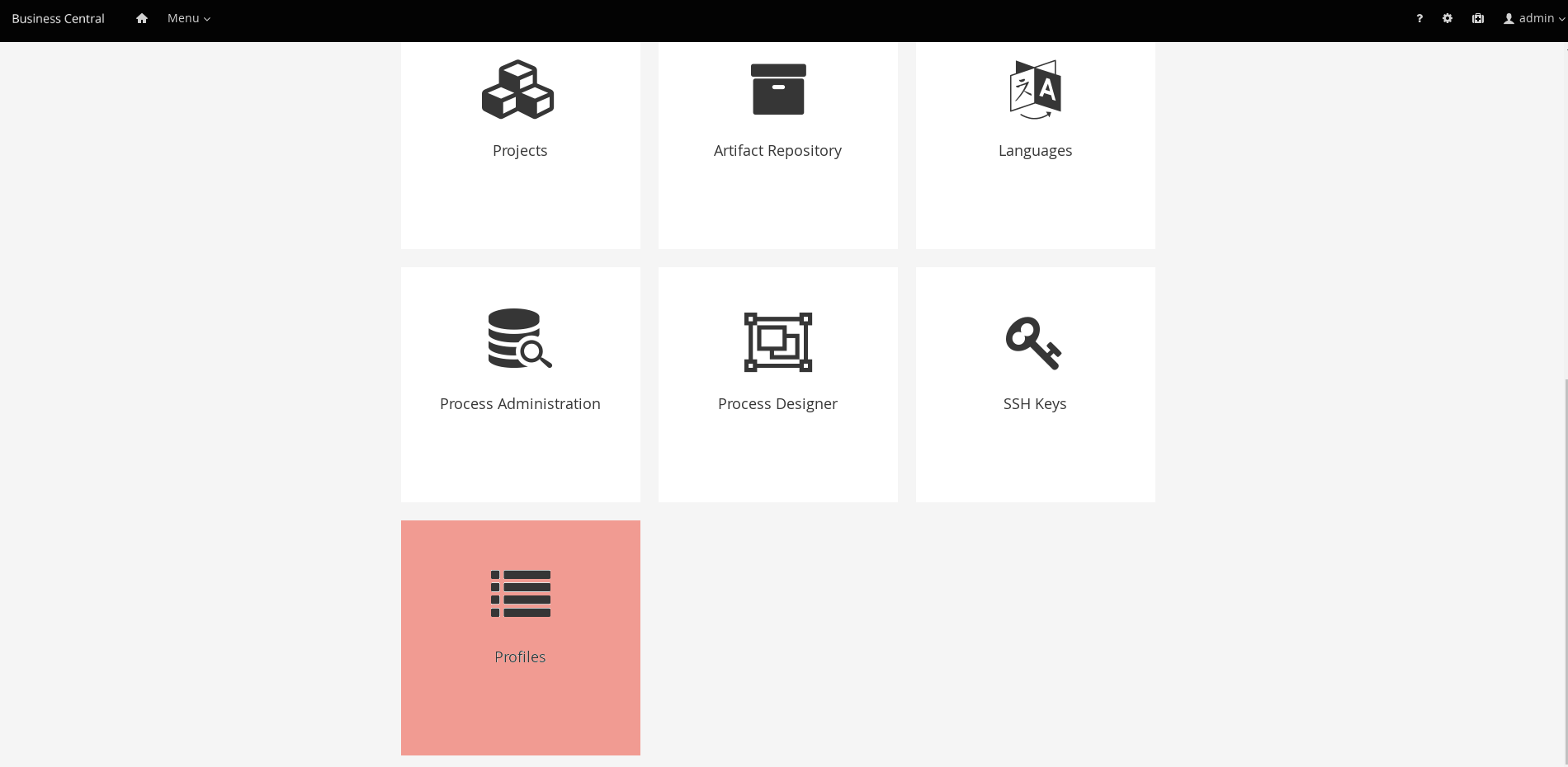

Business Central is is a full featured web application for the visual composition of custom business rules and processes.

-

UberFire is a web-based workbench framework inspired by Eclipse Rich Client Platform.

The 7.x series will follow a more agile approach with more regular and iterative releases. We plan to do some bigger changes than normal for a series of minor releases, and users need to be aware those are coming before adopting.

-

UI sections and links will become object oriented, rather than task oriented. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object-oriented_user_interface

-

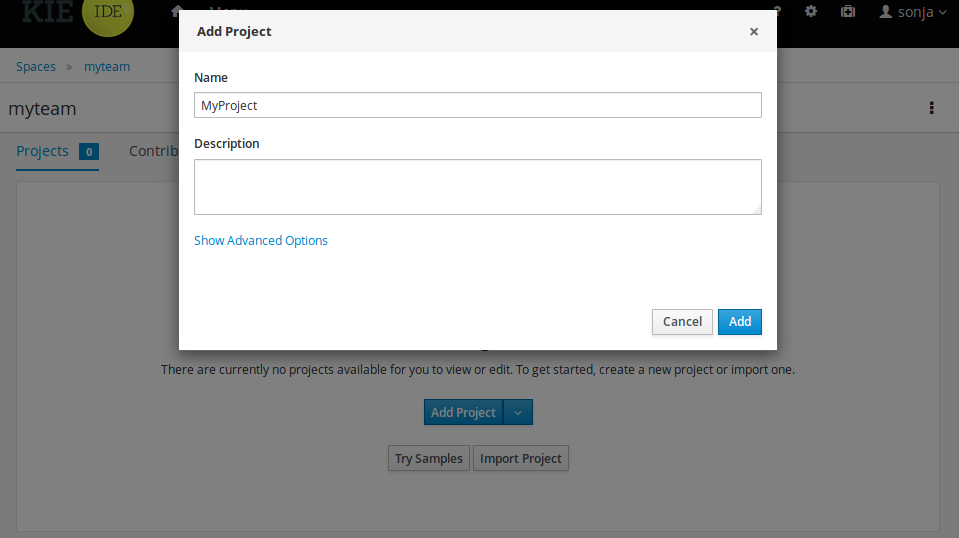

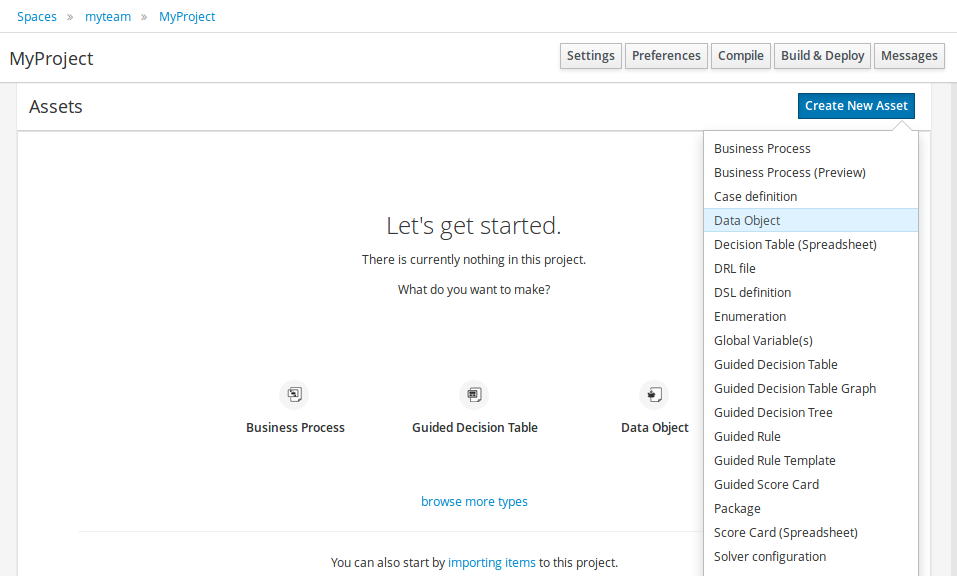

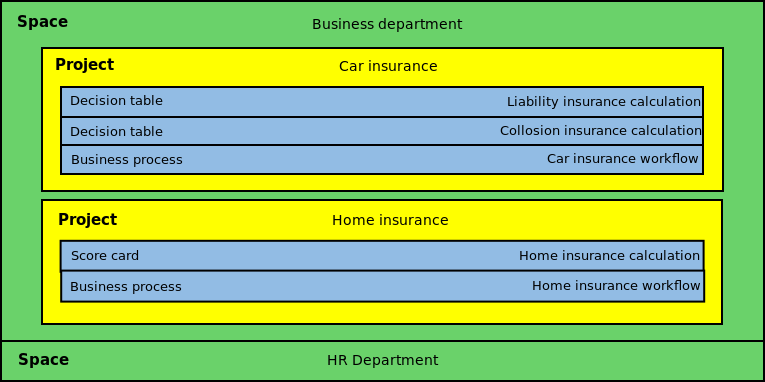

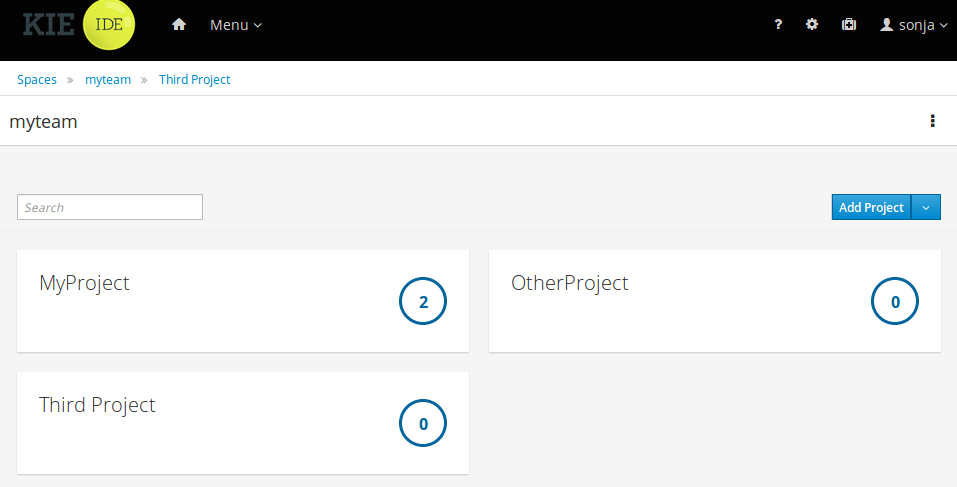

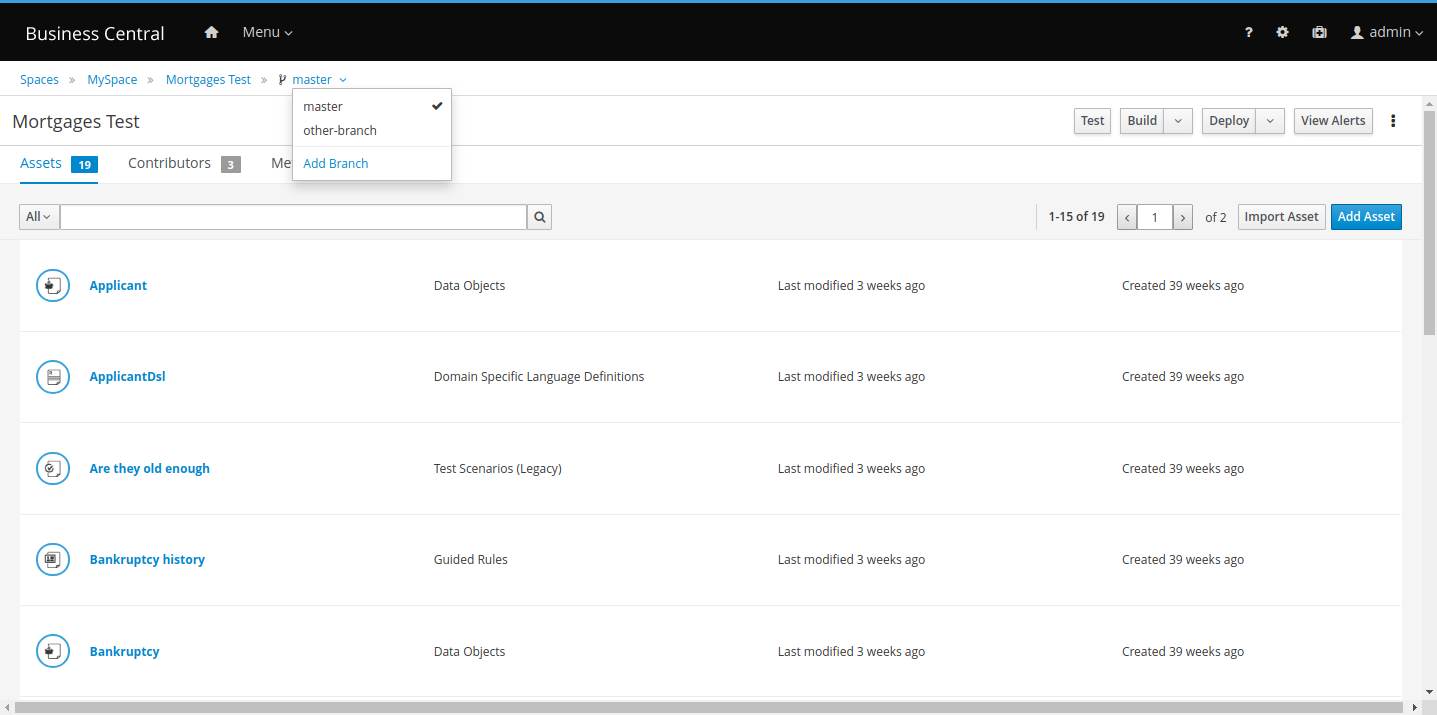

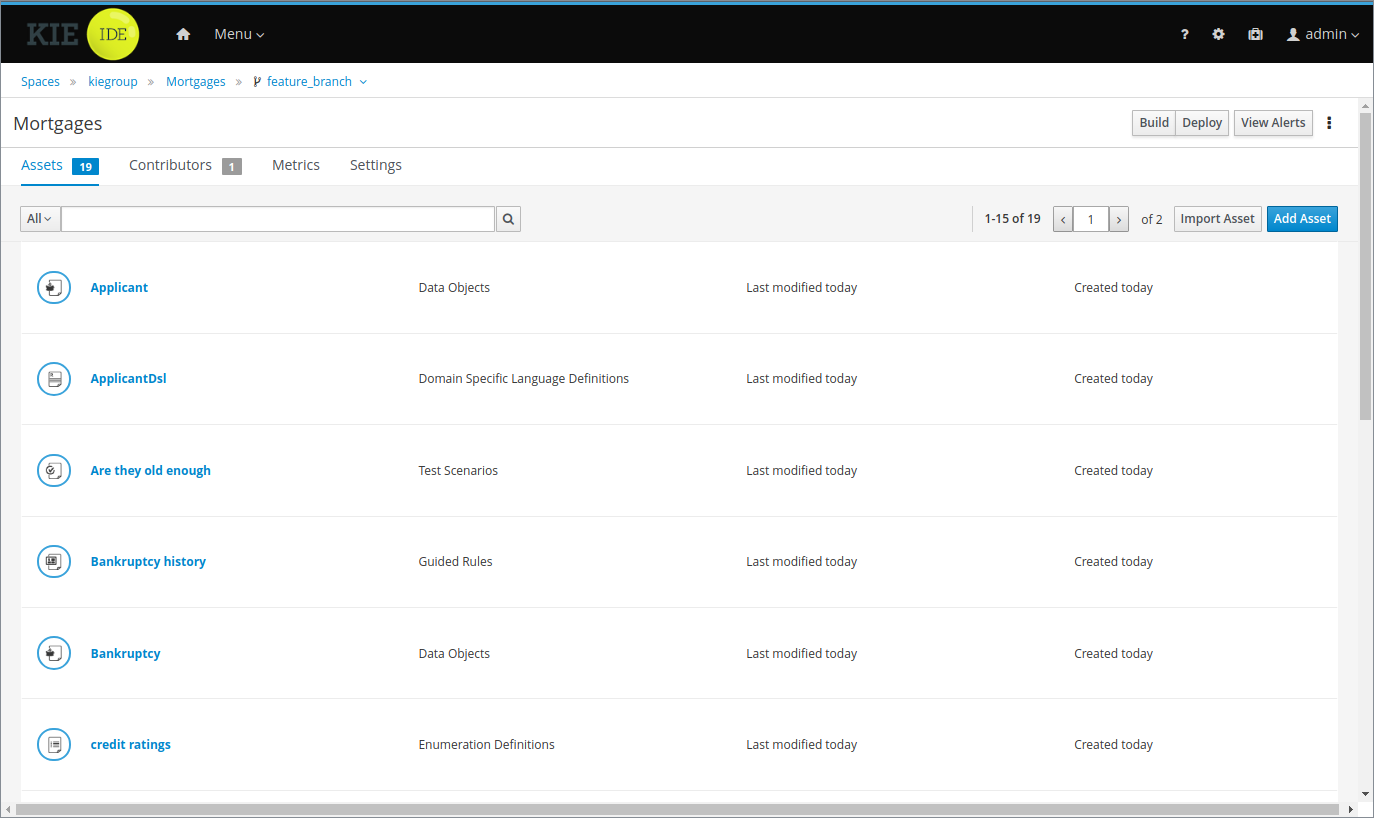

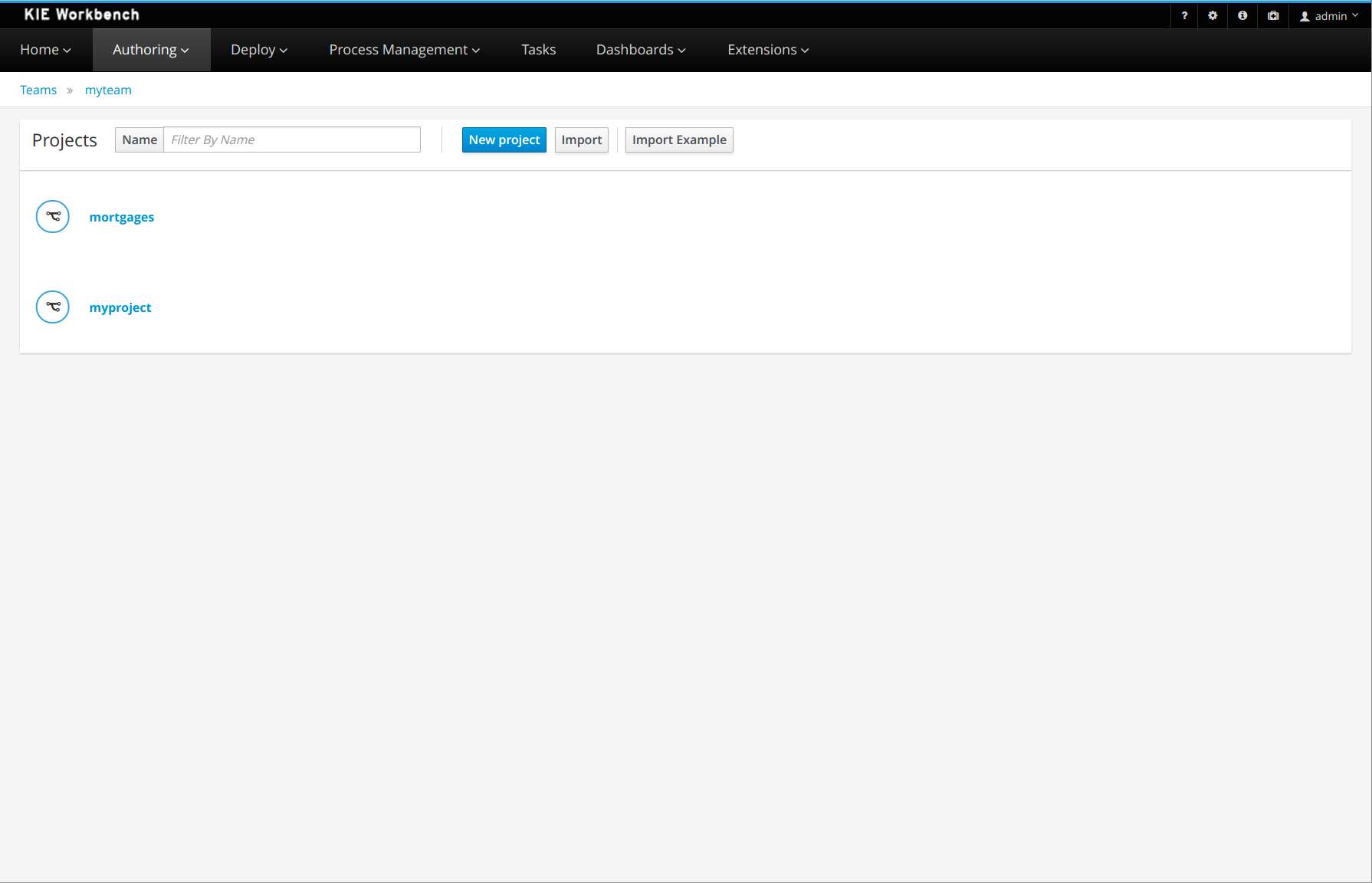

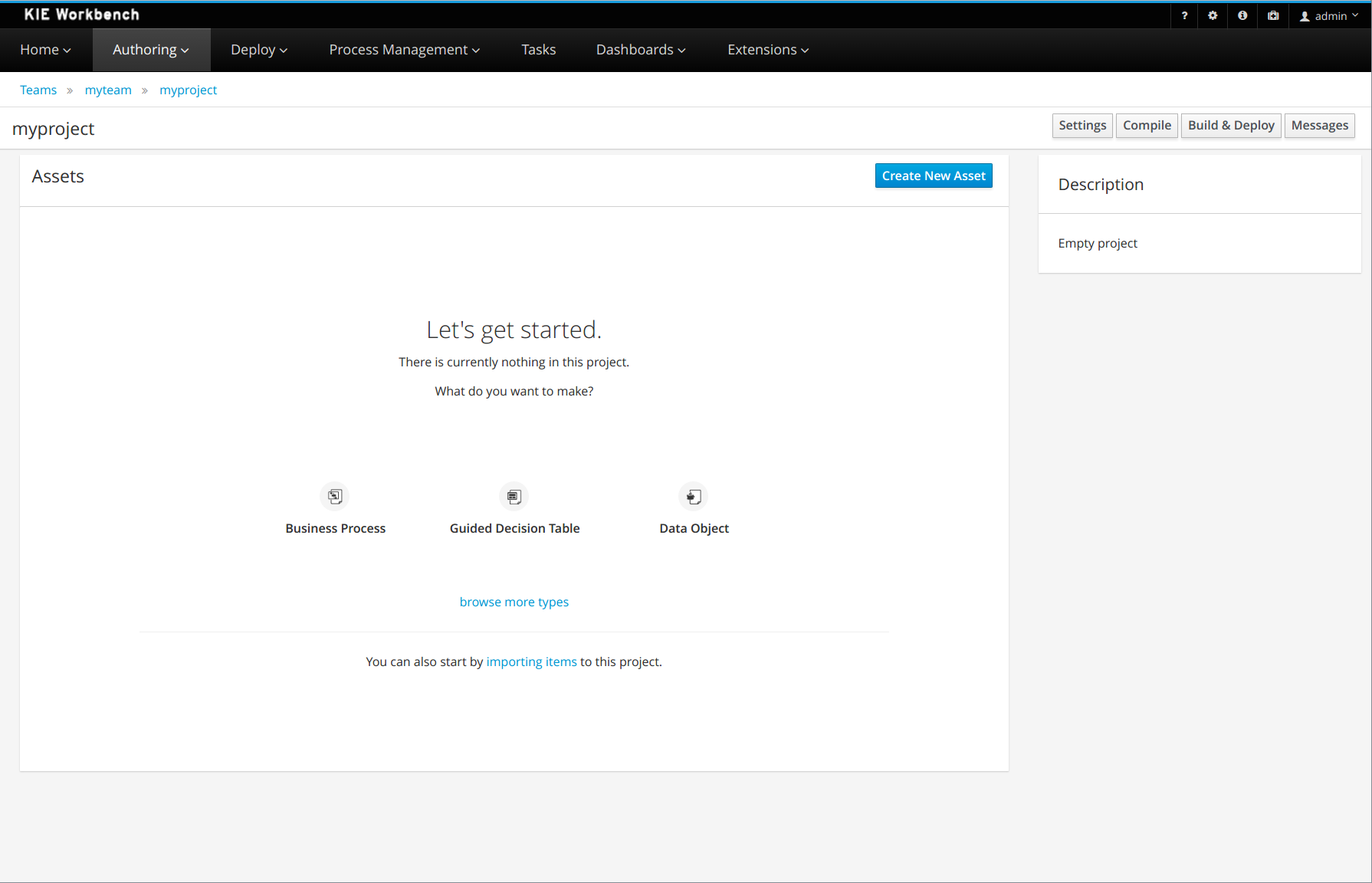

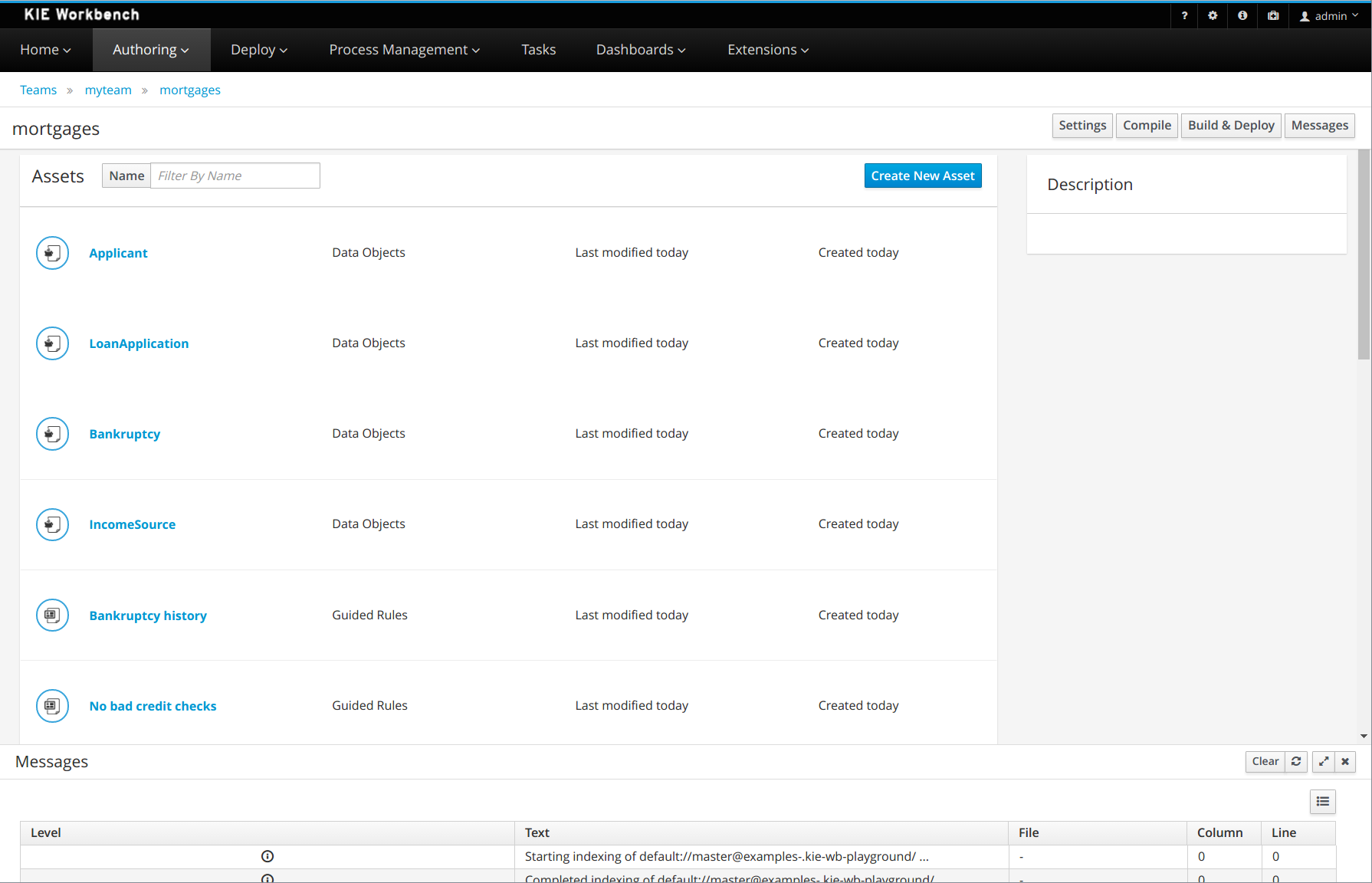

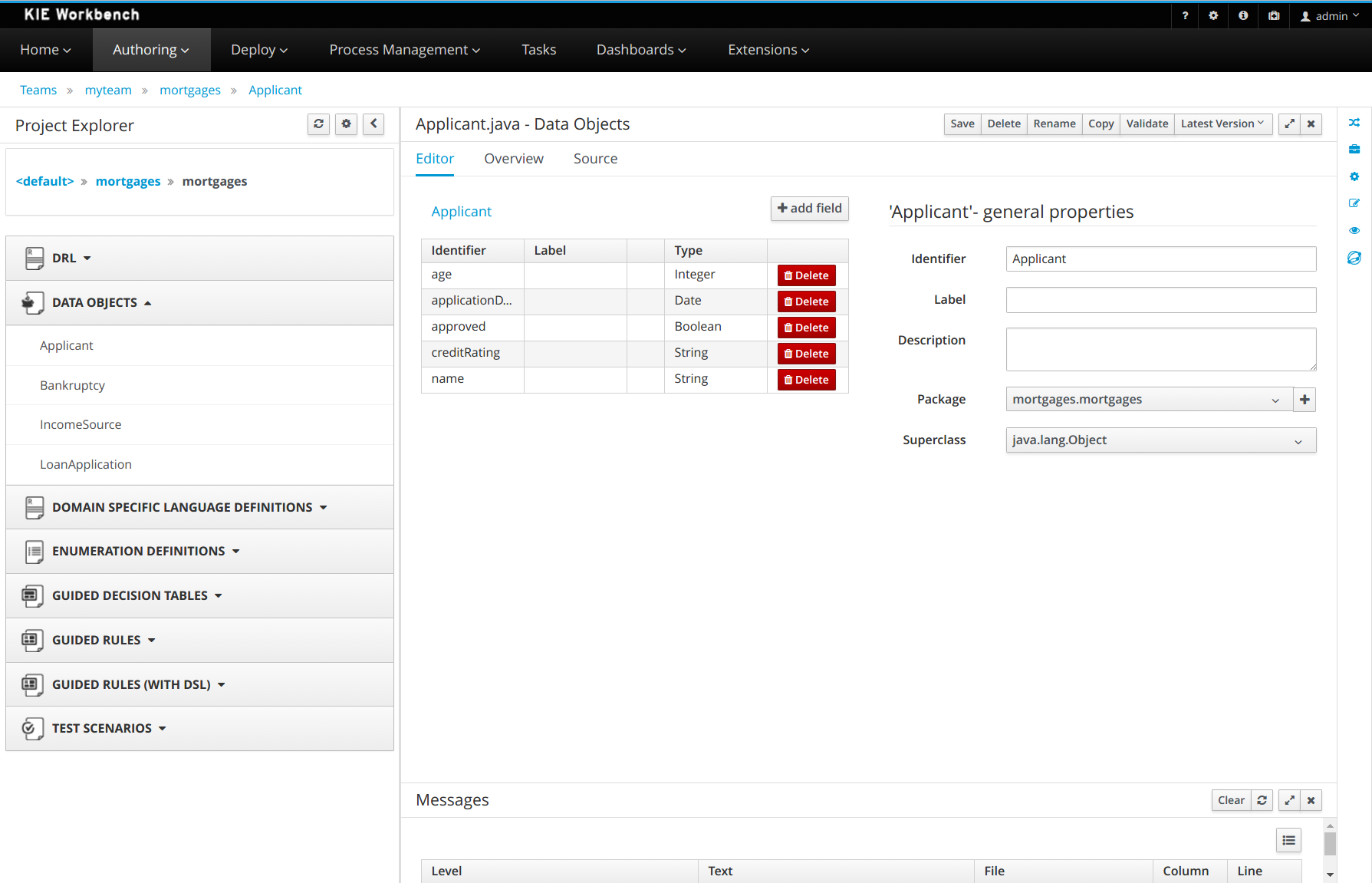

Authoring/Library will become project oriented, rather than repository oriented. You’ll create, browse and open projects rather than repositories. The repository concept will be pushed lower, for instance it’ll be created automaticaly when you create the projcet.

-

The old form modeller will be removed and only the new one made available. Although old forms will continue to render.

-

The new designer will continue to mature with more nodes and improved UXD. Eventually it’ll become the default editor, but we will not remove the old one until there is feature parity in BPMN2 support.

-

Continued UXD improvements in lots of places.

-

We will introduce the AppFormer project, this will be a re-org and consolidation of existing projects and result in some artifact renames. UberFire will become AppFormer-Core, forms, data modeller and dashbuilder will come under AppFormer. Dashbuilder will most likely becalled Appformer-Insight.

The 8.x series will come towards the end of this year. We have ongoing parallel work to introduce concepts of workspaces with improved git support, that will have a built in workflow for forking and pull requests. This will be combined with horizontal scaling and improved high availability. These changes are important for usability and cloud scalability, but too much of a change for a minor release, hence the bump to 8.x

1.2. Getting Involved

We are often asked "How do I get involved". Luckily the answer is simple, just write some code and submit it :) There are no hoops you have to jump through or secret handshakes. We have a very minimal "overhead" that we do request to allow for scalable project development. Below we provide a general overview of the tools and "workflow" we request, along with some general advice.

If you contribute some good work, don’t forget to blog about it :)

1.2.1. Sign up to jboss.org

Signing to jboss.org will give you access to the JBoss wiki, forums and JIRA. Go to https://www.jboss.org/ and click "Register".

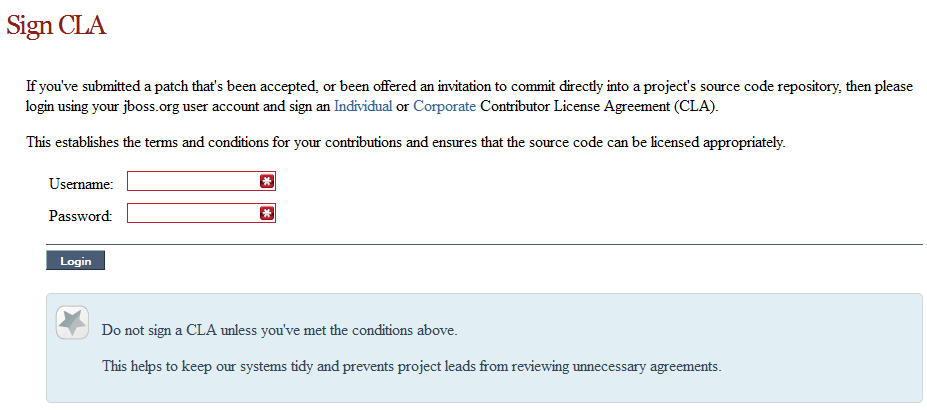

1.2.2. Sign the Contributor Agreement

The only form you need to sign is the contributor agreement, which is fully automated via the web. As the image below says "This establishes the terms and conditions for your contributions and ensures that source code can be licensed appropriately"

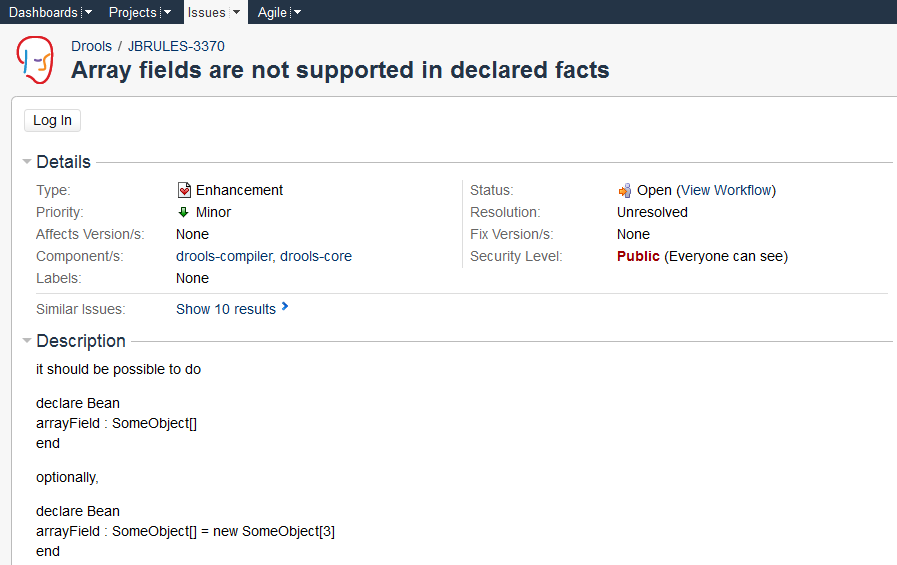

1.2.3. Submitting issues via JIRA

To be able to interact with the core development team you will need to use JIRA, the issue tracker. This ensures that all requests are logged and allocated to a release schedule and all discussions captured in one place. Bug reports, bug fixes, feature requests and feature submissions should all go here. General questions should be undertaken at the mailing lists.

Minor code submissions, like format or documentation fixes do not need an associated JIRA issue created.

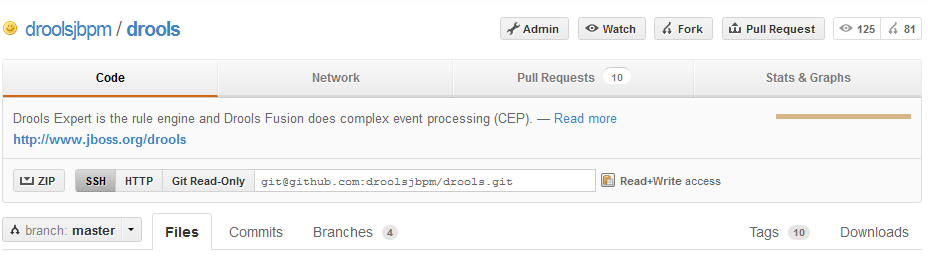

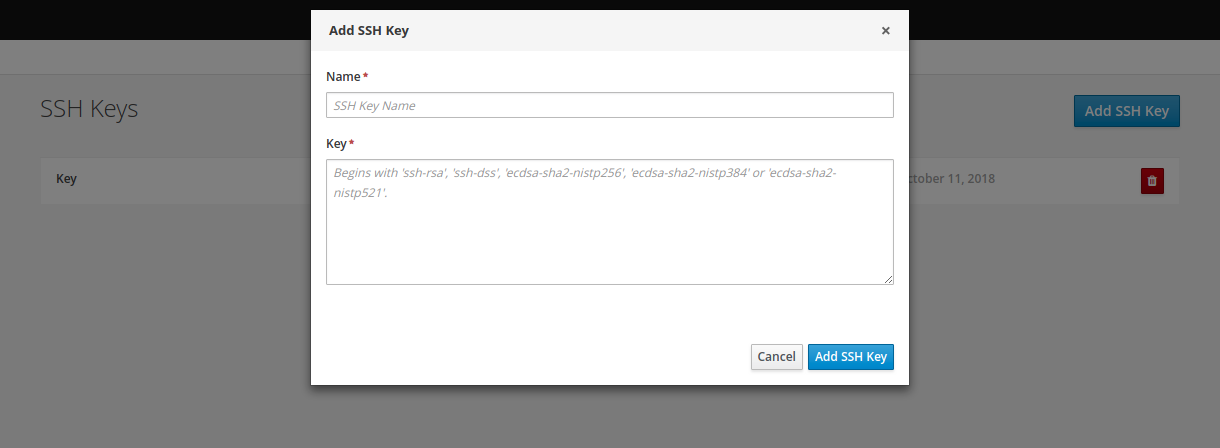

1.2.4. Fork GitHub

With the contributor agreement signed and your requests submitted to JIRA you should now be ready to code :) Create a GitHub account and fork any of the Drools, jBPM or Guvnor repositories. The fork will create a copy in your own GitHub space which you can work on at your own pace. If you make a mistake, don’t worry blow it away and fork again. Note each GitHub repository provides you the clone (checkout) URL, GitHub will provide you URLs specific to your fork.

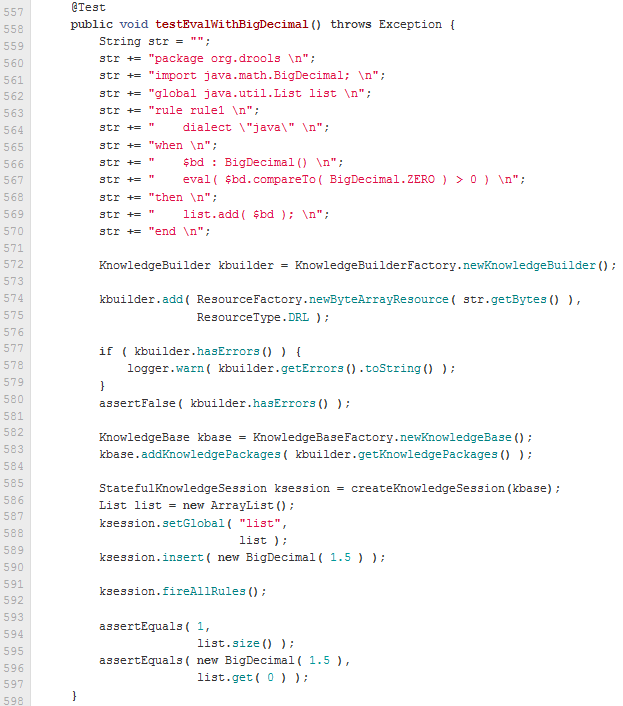

1.2.5. Writing Tests

When writing tests, try and keep them minimal and self contained. We prefer to keep the DRL fragments within the test, as it makes for quicker reviewing. If their are a large number of rules then using a String is not practical so then by all means place them in separate DRL files instead to be loaded from the classpath. If your tests need to use a model, please try to use those that already exist for other unit tests; such as Person, Cheese or Order. If no classes exist that have the fields you need, try and update fields of existing classes before adding a new class.

There are a vast number of tests to look over to get an idea, MiscTest is a good place to start.

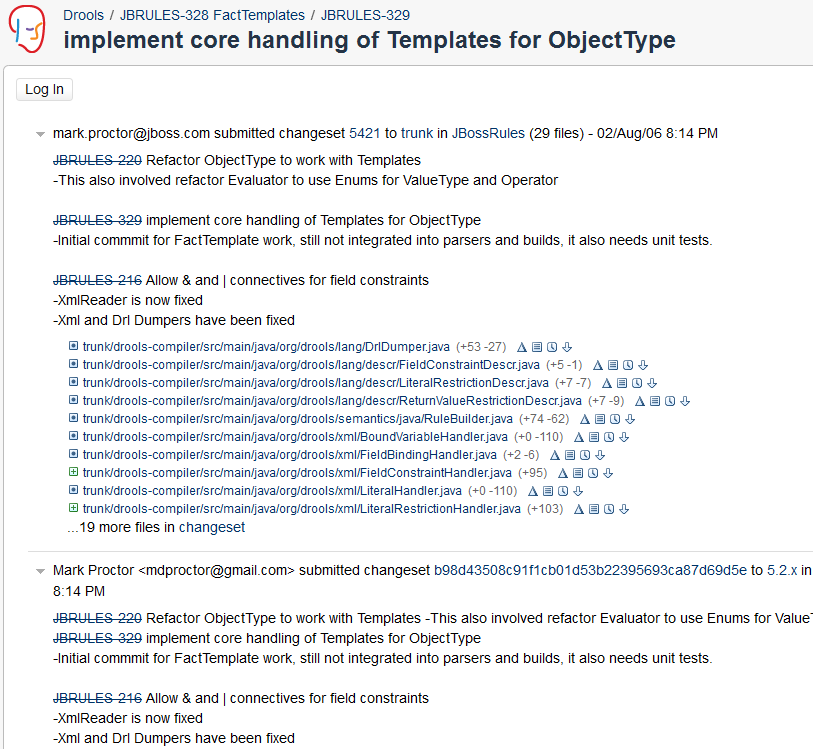

1.2.6. Commit with Correct Conventions

When you commit, make sure you use the correct conventions. The commit must start with the JIRA issue id, such as DROOLS-1946. This ensures the commits are cross referenced via JIRA, so we can see all commits for a given issue in the same place. After the id the title of the issue should come next. Then use a newline, indented with a dash, to provide additional information related to this commit. Use an additional new line and dash for each separate point you wish to make. You may add additional JIRA cross references to the same commit, if it’s appropriate. In general try to avoid combining unrelated issues in the same commit.

Don’t forget to rebase your local fork from the original master and then push your commits back to your fork.

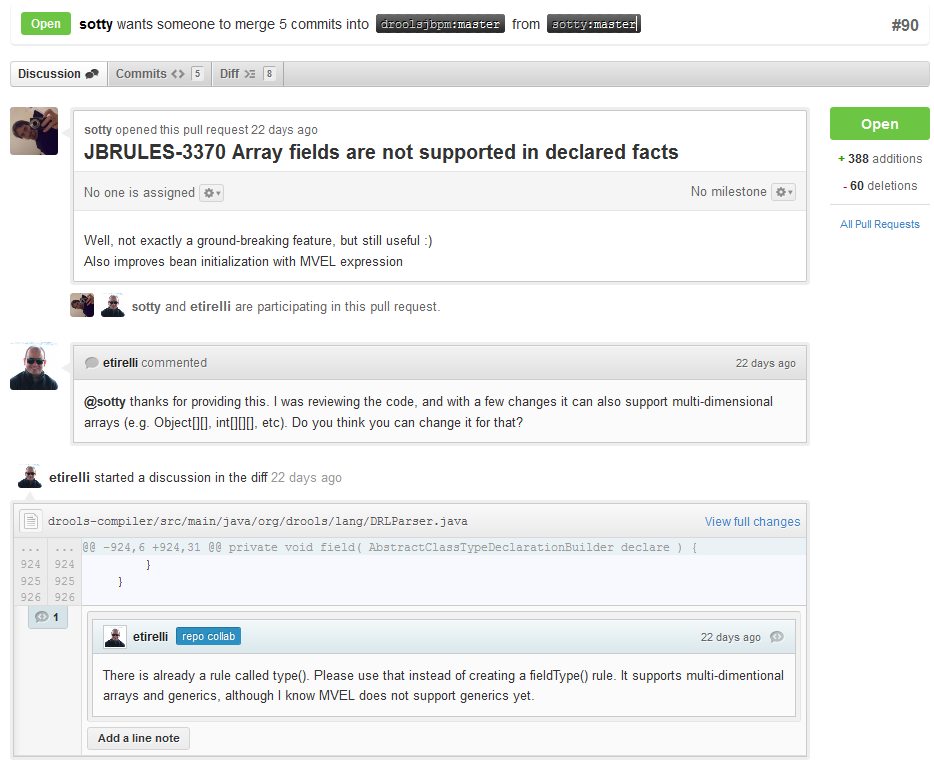

1.2.7. Submit Pull Requests

With your code rebased from original master and pushed to your personal GitHub area, you can now submit your work as a pull request. If you look at the top of the page in GitHub for your work area their will be a "Pull Request" button. Selecting this will then provide a gui to automate the submission of your pull request.

The pull request then goes into a queue for everyone to see and comment on. Below you can see a typical pull request. The pull requests allow for discussions and it shows all associated commits and the diffs for each commit. The discussions typically involve code reviews which provide helpful suggestions for improvements, and allows for us to leave inline comments on specific parts of the code. Don’t be disheartened if we don’t merge straight away, it can often take several revisions before we accept a pull request. Luckily GitHub makes it very trivial to go back to your code, do some more commits and then update your pull request to your latest and greatest.

It can take time for us to get round to responding to pull requests, so please be patient. Submitted tests that come with a fix will generally be applied quite quickly, where as just tests will often way until we get time to also submit that with a fix. Don’t forget to rebase and resubmit your request from time to time, otherwise over time it will have merge conflicts and core developers will general ignore those.

1.3. Installation and Setup (Core and IDE)

1.3.1. Installing and using

Drools provides an Eclipse-based IDE (which is optional), but at its core only Java 1.5 (Java SE) is required.

A simple way to get started is to download and install the Eclipse plug-in - this will also require the Eclipse GEF framework to be installed (see below, if you don’t have it installed already). This will provide you with all the dependencies you need to get going: you can simply create a new rule project and everything will be done for you. Refer to the chapter on Business Central and IDE for detailed instructions on this. Installing the Eclipse plug-in is generally as simple as unzipping a file into your Eclipse plug-in directory.

Use of the Eclipse plug-in is not required. Rule files are just textual input (or spreadsheets as the case may be) and the IDE (also known as Business Central) is just a convenience. People have integrated the Drools engine in many ways, there is no "one size fits all".

Alternatively, you can download the binary distribution, and include the relevant JARs in your projects classpath.

1.3.1.1. Dependencies and JARs

Drools is broken down into a few modules, some are required during rule development/compiling, and some are required at runtime. In many cases, people will simply want to include all the dependencies at runtime, and this is fine. It allows you to have the most flexibility. However, some may prefer to have their "runtime" stripped down to the bare minimum, as they will be deploying rules in binary form - this is also possible. The core Drools engine can be quite compact, and only requires a few 100 kilobytes across 3 JAR files.

The following is a description of the important libraries that make up JBoss Drools

-

knowledge-api.jar - this provides the interfaces and factories. It also helps clearly show what is intended as a user API and what is just an engine API.

-

knowledge-internal-api.jar - this provides internal interfaces and factories.

-

drools-core.jar - this is the core Drools engine, runtime component. Contains both the RETE engine and the LEAPS engine. This is the only runtime dependency if you are pre-compiling rules (and deploying via Package or RuleBase objects).

-

drools-compiler.jar - this contains the compiler/builder components to take rule source, and build executable rule bases. This is often a runtime dependency of your application, but it need not be if you are pre-compiling your rules. This depends on drools-core.

-

drools-jsr94.jar - this is the JSR-94 compliant implementation, this is essentially a layer over the drools-compiler component. Note that due to the nature of the JSR-94 specification, not all features are easily exposed via this interface. In some cases, it will be easier to go direct to the Drools API, but in some environments the JSR-94 is mandated.

-

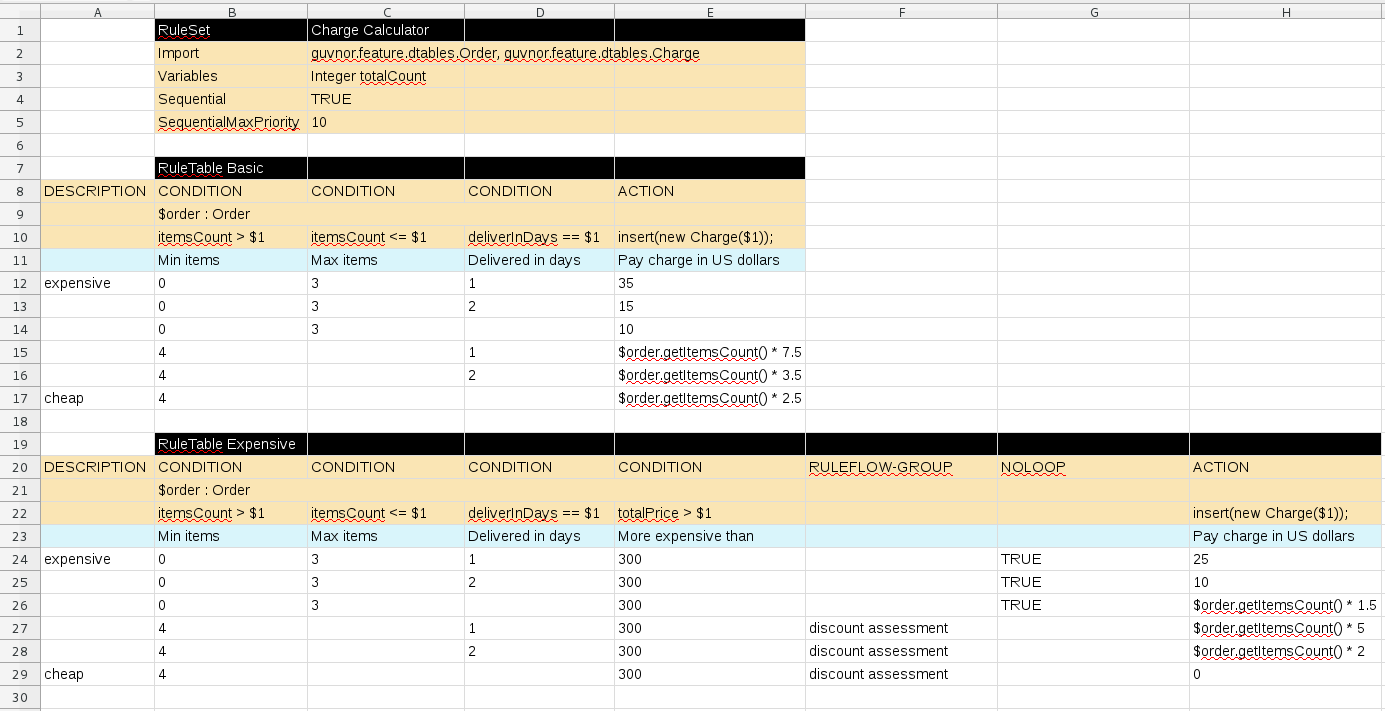

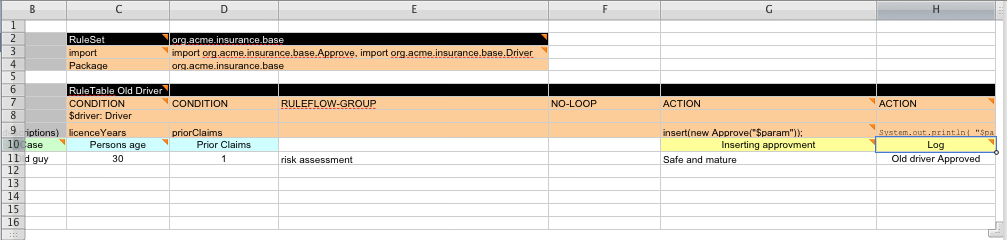

drools-decisiontables.jar - this is the decision tables 'compiler' component, which uses the drools-compiler component. This supports both excel and CSV input formats.

There are quite a few other dependencies which the above components require, most of which are for the drools-compiler, drools-jsr94 or drools-decisiontables module. Some key ones to note are "POI" which provides the spreadsheet parsing ability, and "antlr" which provides the parsing for the rule language itself.

| if you are using Drools in J2EE or servlet containers and you come across classpath issues with "JDT", then you can switch to the janino compiler. Set the system property "drools.compiler": For example: -Ddrools.compiler=JANINO. |

For up to date info on dependencies in a release, consult the released POMs, which can be found on the Maven repository.

1.3.1.2. Use with Maven, Gradle, Ivy, Buildr or Ant

The JARs are also available in the central Maven repository (and also in https://repository.jboss.org/nexus/index.html#nexus-search;gavorg.drools~[the JBoss Maven repository]).

If you use Maven, add KIE and Drools dependencies in your project’s pom.xml like this:

<dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.drools</groupId>

<artifactId>drools-bom</artifactId>

<type>pom</type>

<version>...</version>

<scope>import</scope>

</dependency>

...

</dependencies>

</dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.kie</groupId>

<artifactId>kie-api</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.drools</groupId>

<artifactId>drools-compiler</artifactId>

<scope>runtime</scope>

</dependency>

...

<dependencies>This is similar for Gradle, Ivy and Buildr. To identify the latest version, check the Maven repository.

If you’re still using Ant (without Ivy), copy all the JARs from the download zip’s binaries directory and manually verify that your classpath doesn’t contain duplicate JARs.

1.3.1.3. Runtime

The "runtime" requirements mentioned here are if you are deploying rules as their binary form (either as KnowledgePackage objects, or KnowledgeBase objects etc). This is an optional feature that allows you to keep your runtime very light. You may use drools-compiler to produce rule packages "out of process", and then deploy them to a runtime system. This runtime system only requires drools-core.jar and knowledge-api for execution. This is an optional deployment pattern, and many people do not need to "trim" their application this much, but it is an ideal option for certain environments.

1.3.1.4. Installing IDE (Rule Workbench)

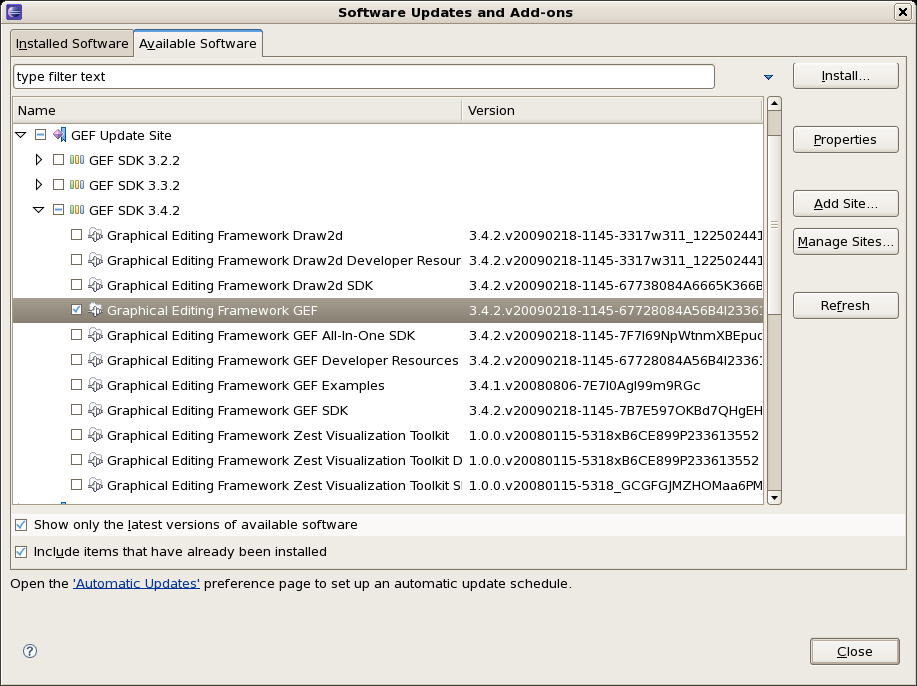

The rule workbench (for Eclipse) requires that you have Eclipse 3.4 or greater, as well as Eclipse GEF 3.4 or greater. You can install it either by downloading the plug-in or using the update site.

Another option is to use the JBoss IDE, which comes with all the plug-in requirements pre packaged, as well as a choice of other tools separate to rules. You can choose just to install rules from the "bundle" that JBoss IDE ships with.

Installing GEF (a required dependency)

GEF is the Eclipse Graphical Editing Framework, which is used for graph viewing components in the plug-in.

If you don’t have GEF installed, you can install it using the built in update mechanism (or downloading GEF from the Eclipse.org website not recommended). JBoss IDE has GEF already, as do many other "distributions" of Eclipse, so this step may be redundant for some people.

Open the Help→Software updates…→Available Software→Add Site… from the help menu. Location is:

http://download.eclipse.org/tools/gef/updates/releases/Next you choose the GEF plug-in:

Press next, and agree to install the plug-in (an Eclipse restart may be required). Once this is completed, then you can continue on installing the rules plug-in.

Installing GEF from zip file

To install from the zip file, download and unzip the file. Inside the zip you will see a plug-in directory, and the plug-in JAR itself. You place the plug-in JAR into your Eclipse applications plug-in directory, and restart Eclipse.

Installing Drools plug-in from zip file

Download the Drools Eclipse IDE plugin from the link below. Unzip the downloaded file in your main eclipse folder (do not just copy the file there, extract it so that the feature and plugin JARs end up in the features and plugin directory of eclipse) and (re)start Eclipse.

To check that the installation was successful, try opening the Drools perspective: Click the 'Open Perspective' button in the top right corner of your Eclipse window, select 'Other…' and pick the Drools perspective. If you cannot find the Drools perspective as one of the possible perspectives, the installation probably was unsuccessful. Check whether you executed each of the required steps correctly: Do you have the right version of Eclipse (3.4.x)? Do you have Eclipse GEF installed (check whether the org.eclipse.gef_3.4..jar exists in the plugins directory in your eclipse root folder)? Did you extract the Drools Eclipse plugin correctly (check whether the org.drools.eclipse_.jar exists in the plugins directory in your eclipse root folder)? If you cannot find the problem, try contacting us (e.g. on irc or on the user mailing list), more info can be found no our homepage here:

Drools Runtimes

A Drools runtime is a collection of JARs on your file system that represent one specific release of the Drools project JARs. To create a runtime, you must point the IDE to the release of your choice. If you want to create a new runtime based on the latest Drools project JARs included in the plugin itself, you can also easily do that. You are required to specify a default Drools runtime for your Eclipse workspace, but each individual project can override the default and select the appropriate runtime for that project specifically.

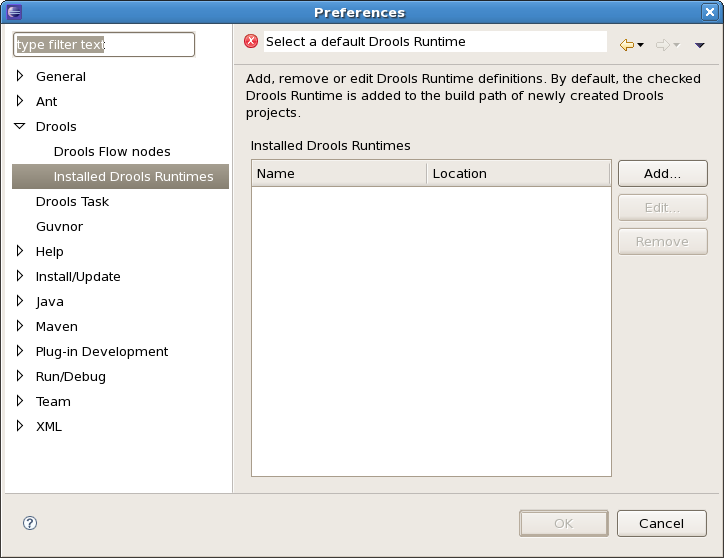

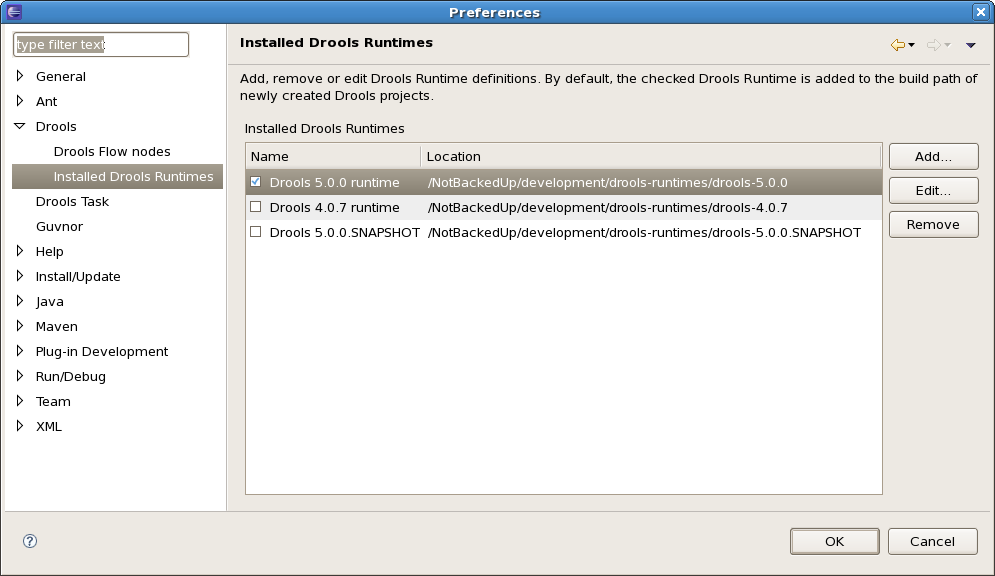

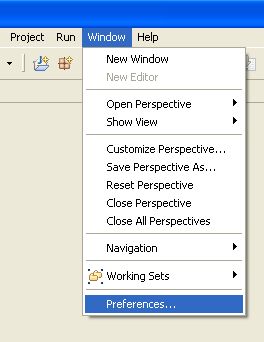

You are required to define one or more Drools runtimes using the Eclipse preferences view. To open up your preferences, in the menu Window select the Preferences menu item. A new preferences dialog should show all your preferences. On the left side of this dialog, under the Drools category, select "Installed Drools runtimes". The panel on the right should then show the currently defined Drools runtimes. If you have not yet defined any runtimes, it should like something like the figure below.

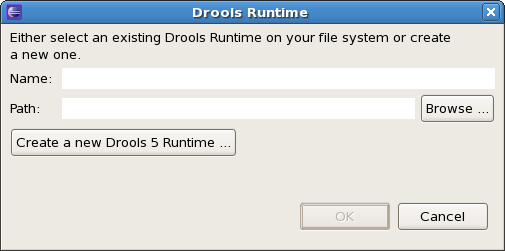

To define a new Drools runtime, click on the add button. A dialog as shown below should pop up, requiring the name for your runtime and the location on your file system where it can be found.

In general, you have two options:

-

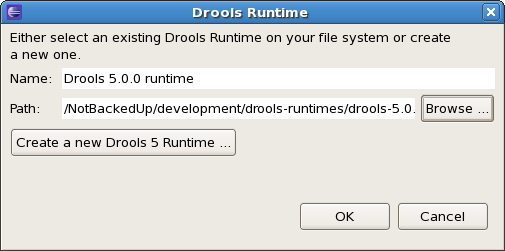

If you simply want to use the default JARs as included in the Drools Eclipse plugin, you can create a new Drools runtime automatically by clicking the "Create a new Drools 5 runtime …" button. A file browser will show up, asking you to select the folder on your file system where you want this runtime to be created. The plugin will then automatically copy all required dependencies to the specified folder. After selecting this folder, the dialog should look like the figure shown below.

-

If you want to use one specific release of the Drools project, you should create a folder on your file system that contains all the necessary Drools libraries and dependencies. Instead of creating a new Drools runtime as explained above, give your runtime a name and select the location of this folder containing all the required JARs.

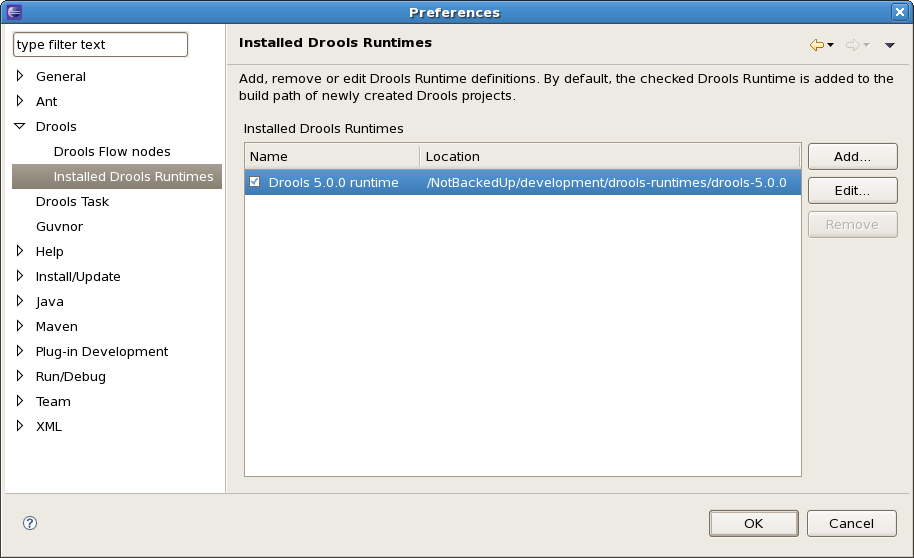

After clicking the OK button, the runtime should show up in your table of installed Drools runtimes, as shown below. Click on checkbox in front of the newly created runtime to make it the default Drools runtime. The default Drools runtime will be used as the runtime of all your Drools project that have not selected a project-specific runtime.

You can add as many Drools runtimes as you need. For example, the screenshot below shows a configuration where three runtimes have been defined: a Drools 4.0.7 runtime, a Drools 5.0.0 runtime and a Drools 5.0.0.SNAPSHOT runtime. The Drools 5.0.0 runtime is selected as the default one.

Note that you will need to restart Eclipse if you changed the default runtime and you want to make sure that all the projects that are using the default runtime update their classpath accordingly.

Whenever you create a Drools project (using the New Drools Project wizard or by converting an existing Java project to a Drools project using the "Convert to Drools Project" action that is shown when you are in the Drools perspective and you right-click an existing Java project), the plugin will automatically add all the required JARs to the classpath of your project.

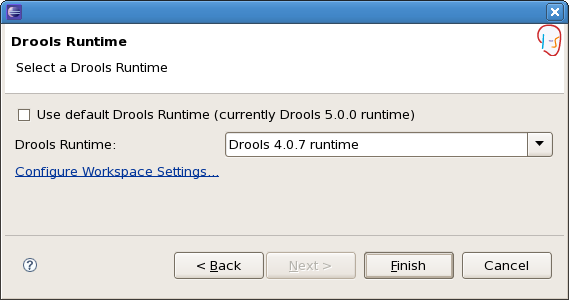

When creating a new Drools project, the plugin will automatically use the default Drools runtime for that project, unless you specify a project-specific one. You can do this in the final step of the New Drools Project wizard, as shown below, by deselecting the "Use default Drools runtime" checkbox and selecting the appropriate runtime in the drop-down box. If you click the "Configure workspace settings …" link, the workspace preferences showing the currently installed Drools runtimes will be opened, so you can add new runtimes there.

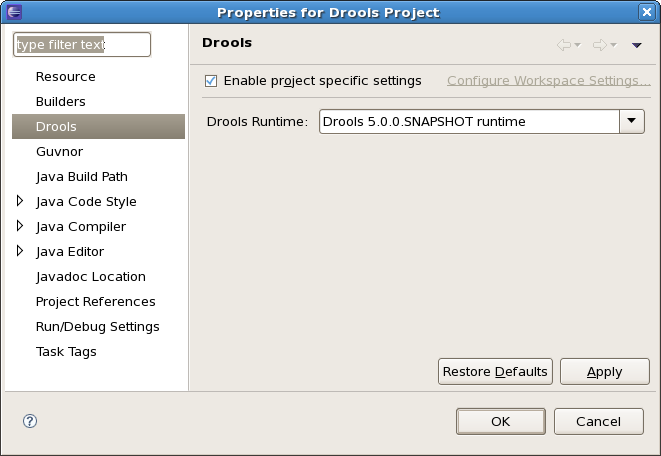

You can change the runtime of a Drools project at any time by opening the project properties (right-click the project and select Properties) and selecting the Drools category, as shown below. Check the "Enable project specific settings" checkbox and select the appropriate runtime from the drop-down box. If you click the "Configure workspace settings …" link, the workspace preferences showing the currently installed Drools runtimes will be opened, so you can add new runtimes there. If you deselect the "Enable project specific settings" checkbox, it will use the default runtime as defined in your global preferences.

1.3.2. Building from source

1.3.2.1. Getting the sources

The source code of each Maven artifact is available in the JBoss Maven repository as a source JAR. The same source JARs are also included in the download zips. However, if you want to build from source, it’s highly recommended to get our sources from our source control.

Git allows you to fork our code, independently make personal changes on it, yet still merge in our latest changes regularly and optionally share your changes with us. To learn more about git, read the free book Git Pro.

1.3.2.2. Building the sources

In essense, building from source is very easy, for example if you want to build the guvnor project:

$ git clone git@github.com:kiegroup/guvnor.git

...

$ cd guvnor

$ mvn clean install -DskipTests -Dfull

...However, there are a lot potential pitfalls, so if you’re serious about building from source and possibly contributing to the project, follow the instructions in the README file in droolsjbpm-build-bootstrap.

1.3.3. Eclipse

1.3.3.1. Importing Eclipse Projects

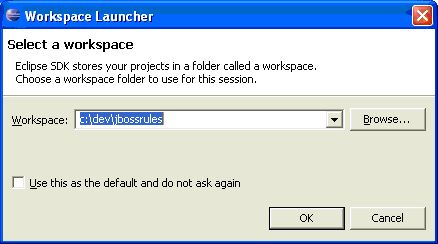

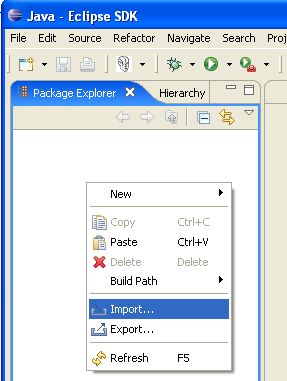

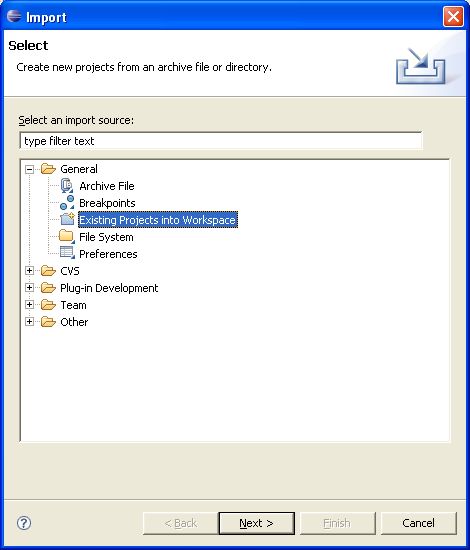

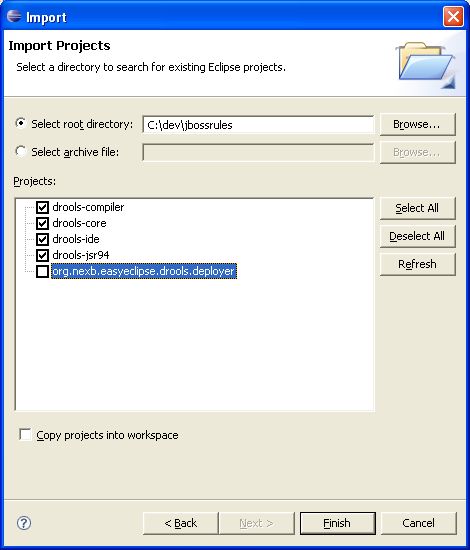

With the Eclipse project files generated they can now be imported into Eclipse. When starting Eclipse open the workspace in the root of your subversion checkout.

When calling mvn install all the project dependencies were downloaded and added to the local Maven repository.

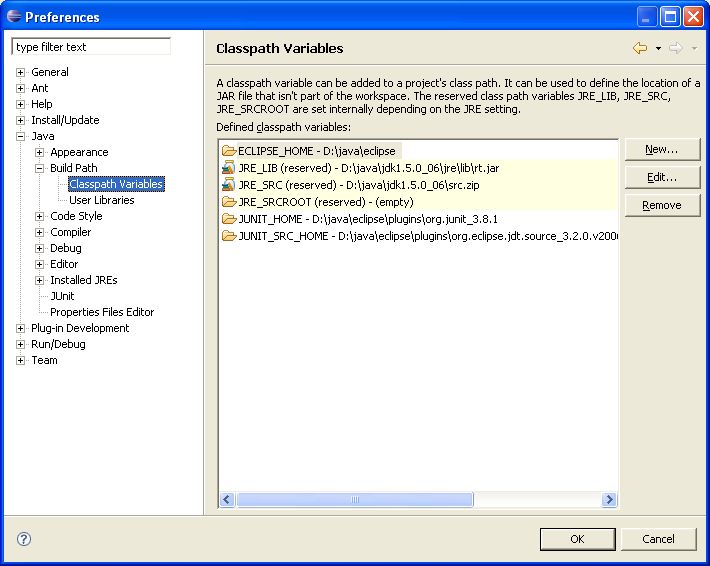

Eclipse cannot find those dependencies unless you tell it where that repository is.

To do this setup an M2_REPO classpath variable.

KIE

KIE is the shared core for Drools and jBPM. It provides a unified methodology and programming model for building, deploying and utilizing resources.

2. KIE

2.1. Overview

2.1.1. Anatomy of Projects

The process of researching an integration knowledge solution for Drools and jBPM has simply used the "kiegroup" group name. This name permeates GitHub accounts and Maven POMs. As scopes broadened and new projects were spun KIE, an acronym for Knowledge Is Everything, was chosen as the new group name. The KIE name is also used for the shared aspects of the system; such as the unified build, deploy and utilization.

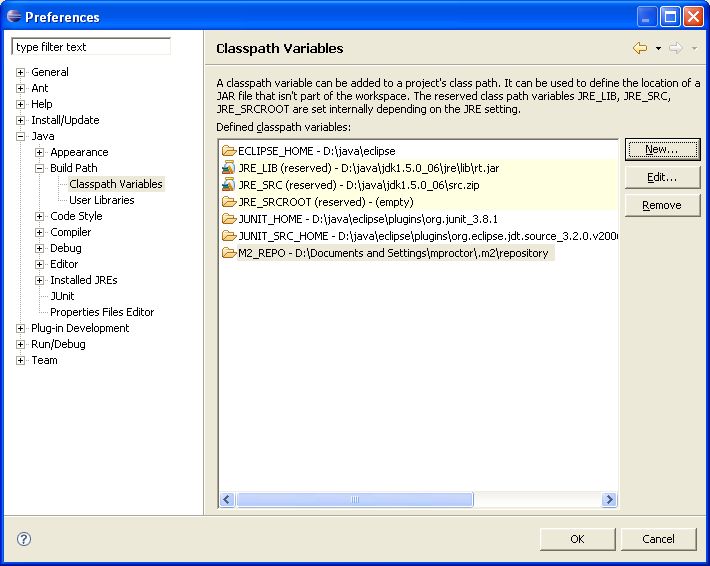

KIE currently consists of the following subprojects:

OptaPlanner, a local search and optimization tool, has been spun off from Drools Planner and is now a top level project with Drools and jBPM. This was a natural evolution as Optaplanner, while having strong Drools integration, has long been independent of Drools.

From the Polymita acquisition, along with other things, comes the powerful Dashboard Builder which provides powerful reporting capabilities. Dashboard Builder is currently a temporary name and after the 6.0 release a new name will be chosen. Dashboard Builder is completely independent of Drools and jBPM and will be used by many projects at JBoss, and hopefully outside of JBoss :)

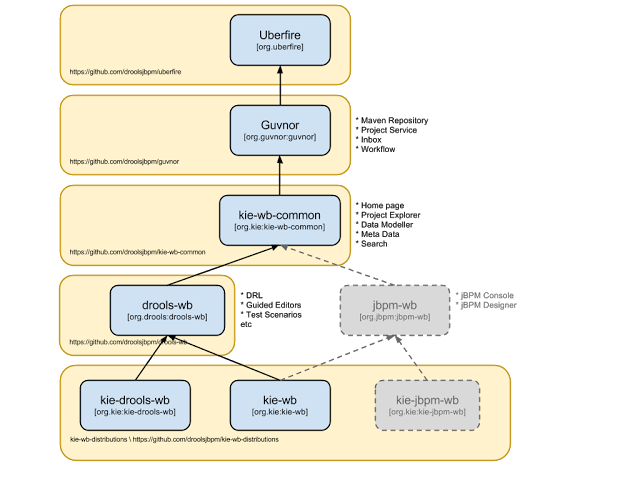

UberFire is the new base Business Central project, spun off from the ground up rewrite. UberFire provides Eclipse-like workbench capabilities, with panels and pages from plugins. The project is independent of Drools and jBPM and anyone can use it as a basis of building flexible and powerful workbenches like Business Central. UberFire will be used for console and workbench development throughout JBoss.

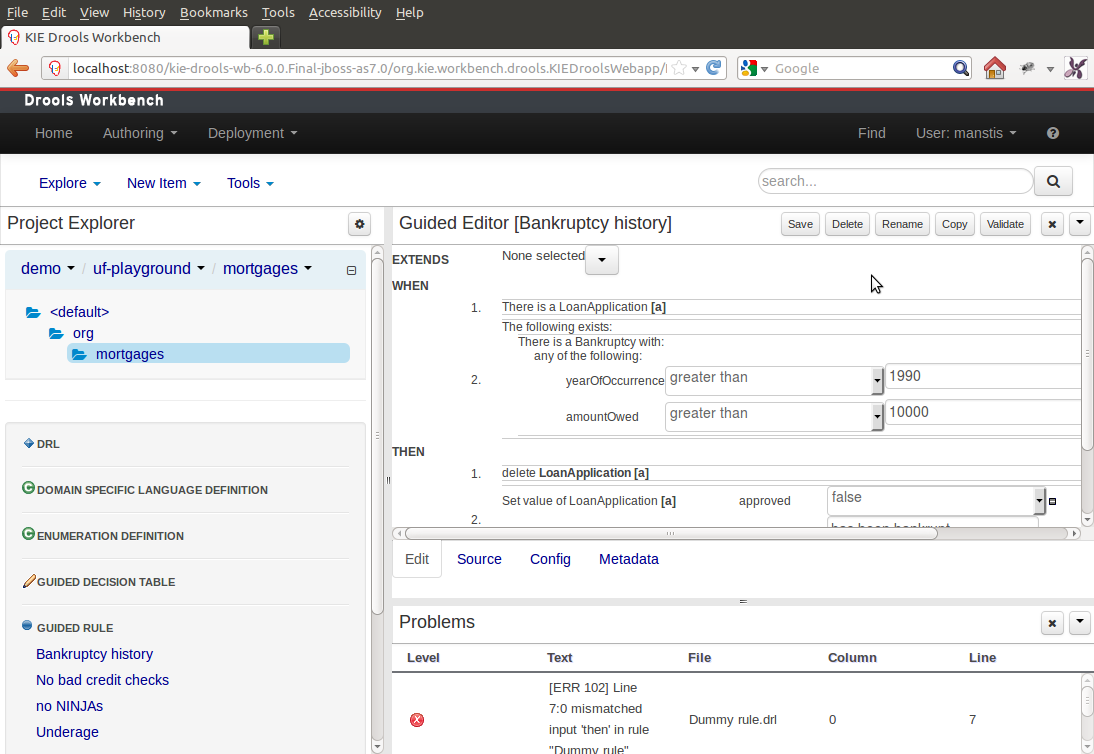

It was determined that the Guvnor brand leaked too much from its intended role; such as the authoring metaphors, like Decision Tables, being considered Guvnor components instead of Drools components. This wasn’t helped by the monolithic projects structure used in 5.x for Guvnor. In 6.0 Guvnor’s focus has been narrowed to encapsulate the set of UberFire plugins that provide the basis for building a web based IDE. Such as Maven integration for building and deploying, management of Maven repositories and activity notifications via inboxes. Drools and jBPM build Business Central distributions using Uberfire as the base and including a set of plugins, such as Guvnor, along with their own plugins for things like decision tables, guided editors, BPMN2 designer, human tasks. Business Central is called business-central.

KIE-WB is the uber workbench that combined all the Guvnor, Drools and jBPM plugins. The jBPM-WB is ghosted out, as it doesn’t actually exist, being made redundant by KIE-WB.

2.1.2. Lifecycles

The different aspects, or life cycles, of working with KIE system, whether it’s Drools or jBPM, can typically be broken down into the following:

-

Author

-

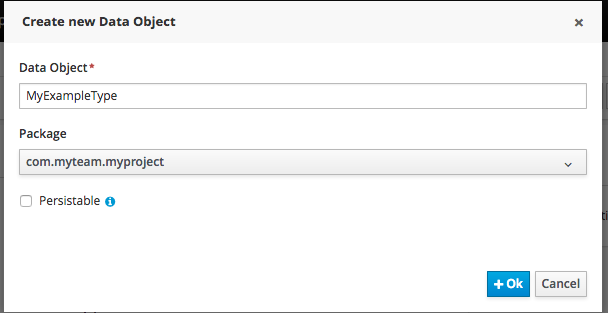

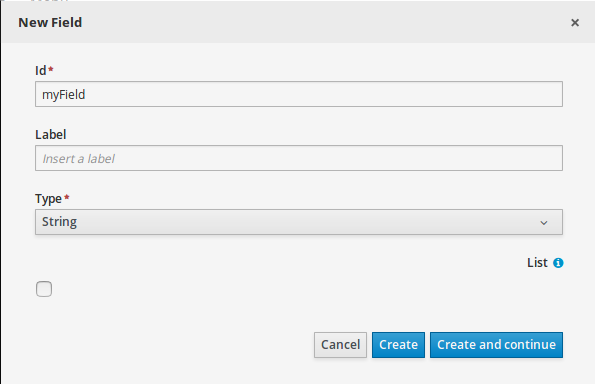

Authoring of knowledge using a UI metaphor, such as: DRL, BPMN2, decision table, class models.

-

-

Build

-

Builds the authored knowledge into deployable units.

-

For KIE this unit is a JAR.

-

-

Test

-

Test KIE knowledge before it’s deployed to the application.

-

-

Deploy

-

Deploys the unit to a location where applications may utilize (consume) them.

-

KIE uses Maven style repository.

-

-

Utilize

-

The loading of a JAR to provide a KIE session (KieSession), for which the application can interact with.

-

KIE exposes the JAR at runtime via a KIE container (KieContainer).

-

KieSessions, for the runtime’s to interact with, are created from the KieContainer.

-

-

Run

-

System interaction with the KieSession, via API.

-

-

Work

-

User interaction with the KieSession, via command line or UI.

-

-

Manage

-

Manage any KieSession or KieContainer.

-

2.1.3. Installation environment options for Drools

With Drools, you can set up a development environment to develop business applications, a runtime environment to run those applications to support decisions, or both.

-

Development environment: Typically consists of one Business Central installation and at least one KIE Server installation. You can use Business Central to design decisions and other artifacts, and you can use KIE Server to execute and test the artifacts that you created.

-

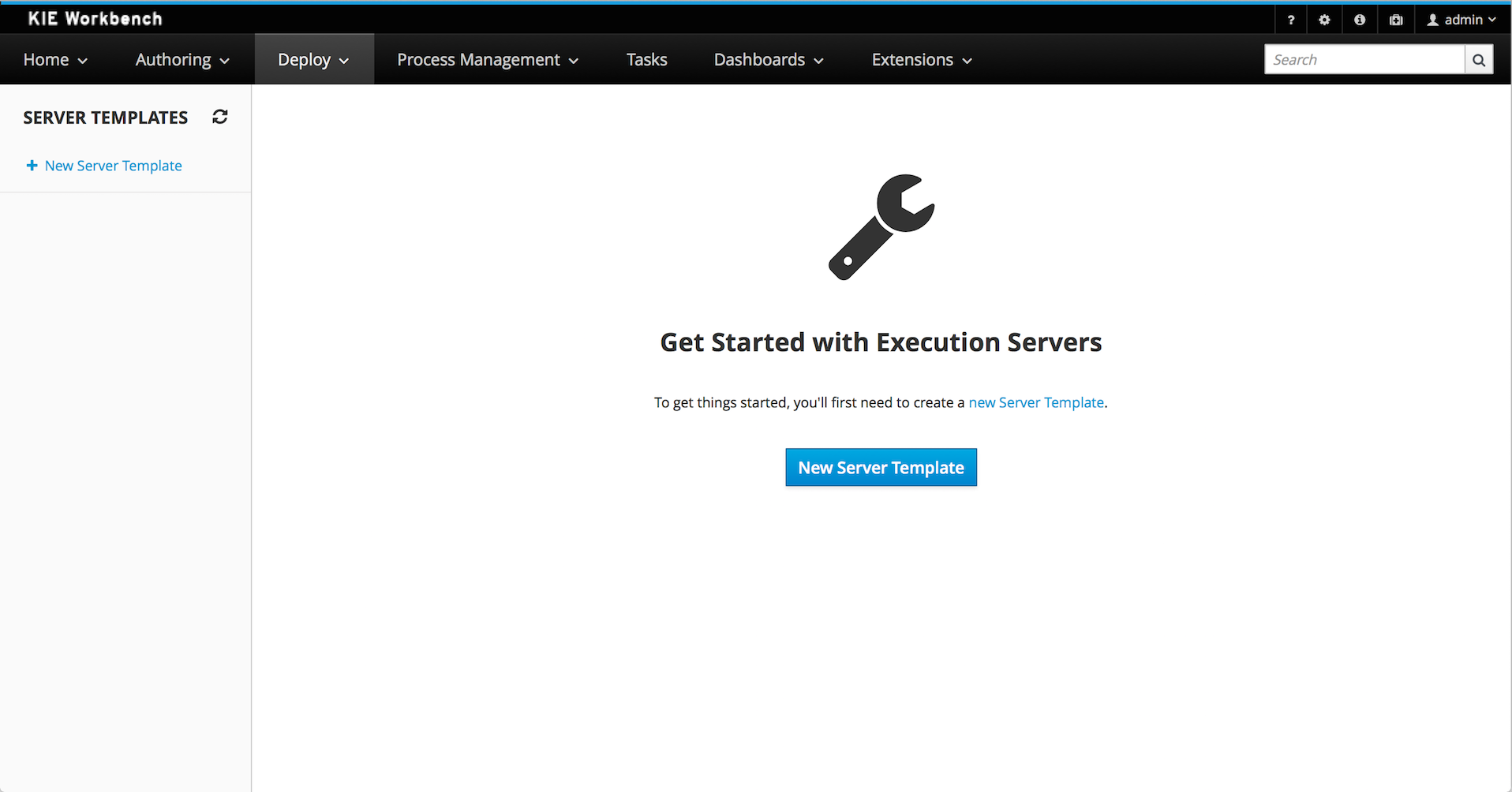

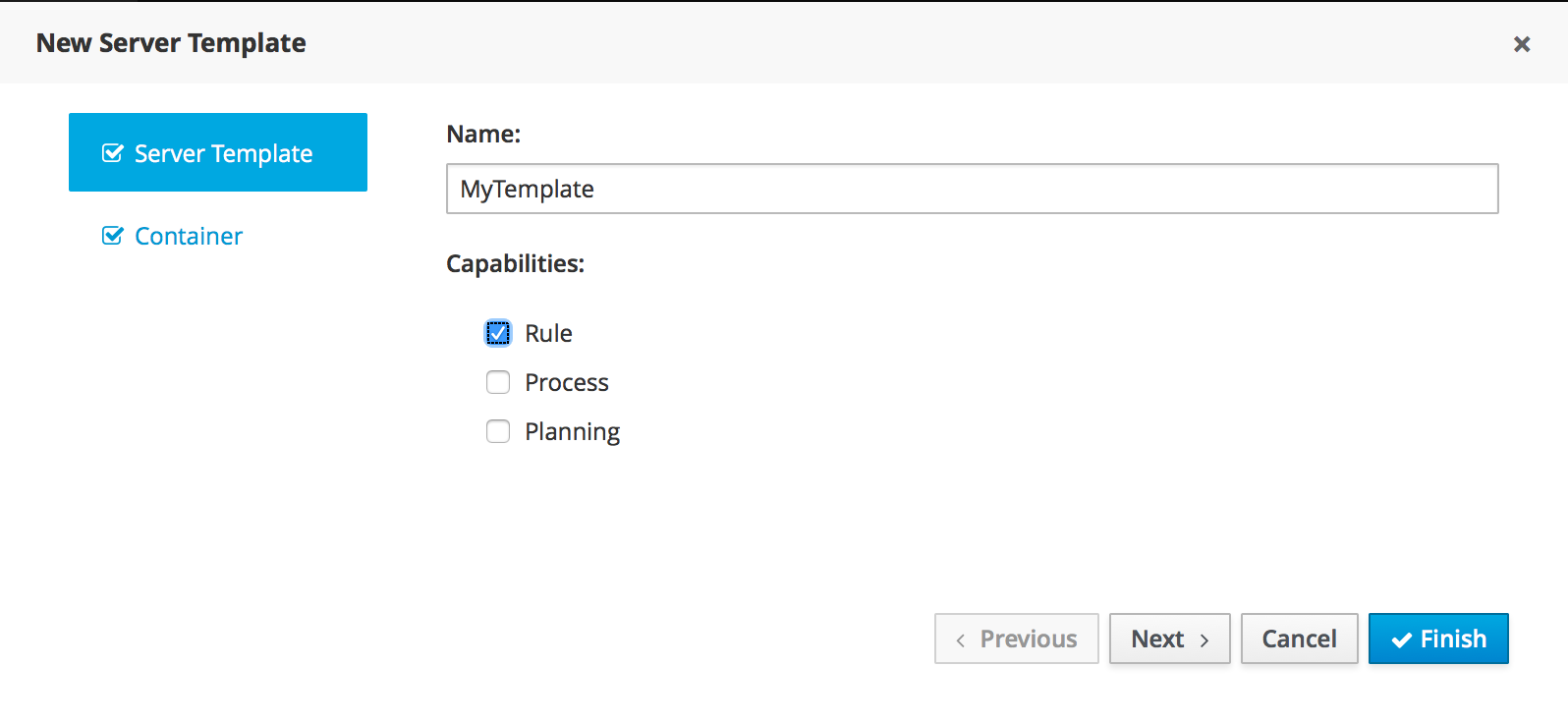

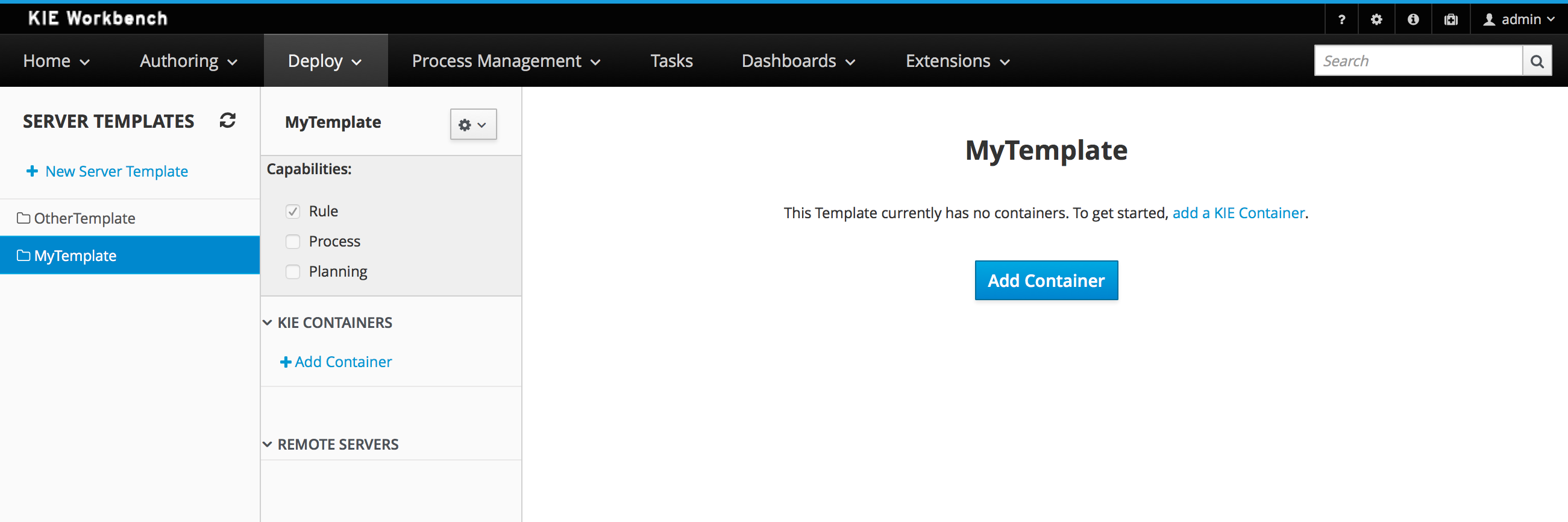

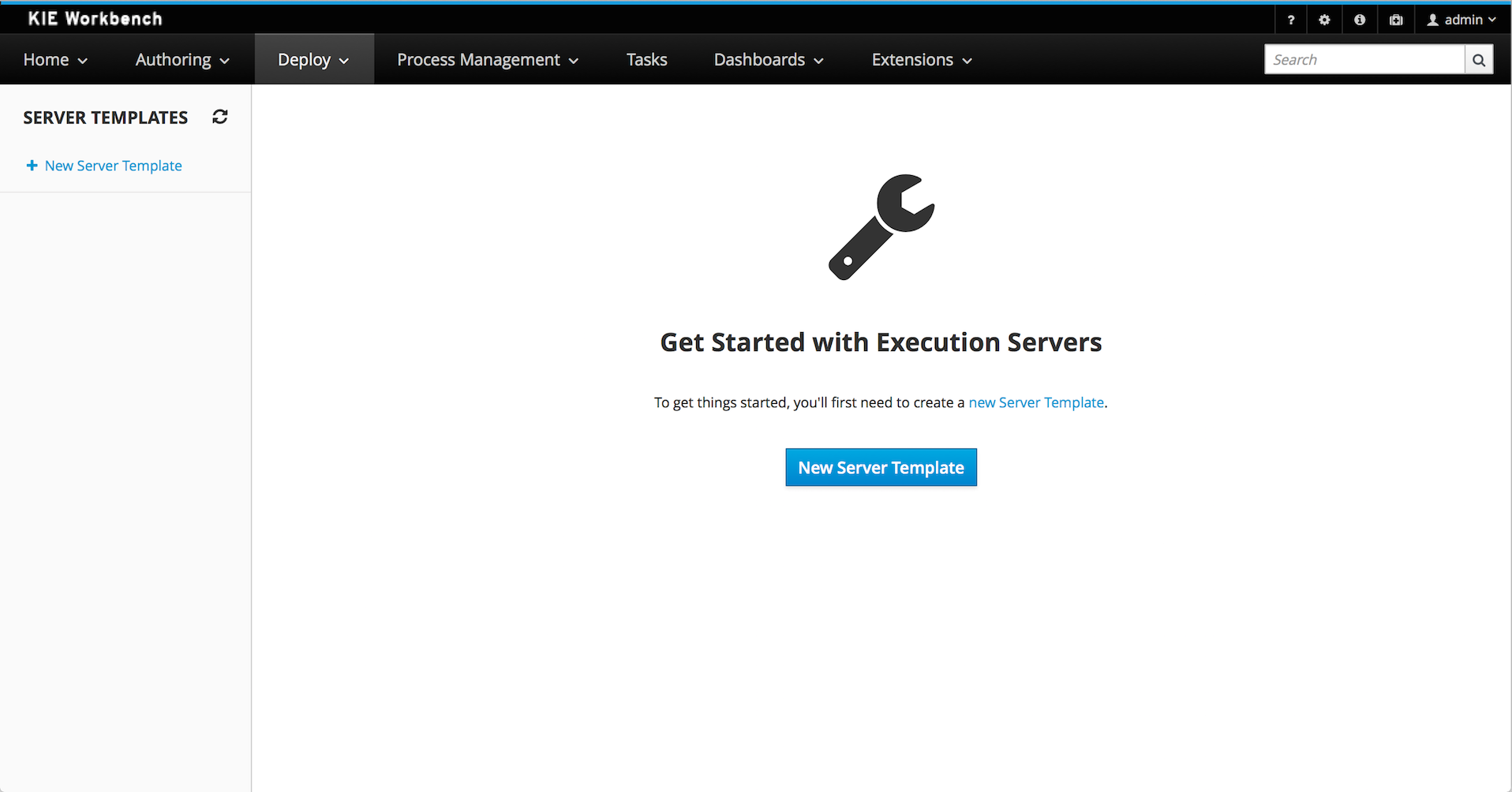

Runtime environment: Consists of one or more KIE Server instances with or without Business Central. Business Central has an embedded Drools controller. If you install Business Central, use the Menu → Deploy → Execution servers page to create and maintain containers. If you want to automate KIE Server management without Business Central, you can use the headless Drools controller.

You can also cluster both development and runtime environments. A clustered development or runtime environment consists of a unified group or "cluster" of two or more servers. The primary benefit of clustering Drools development environments is high availability and enhanced collaboration, while the primary benefit of clustering Drools runtime environments is high availability and load balancing. High availability decreases the chance of a loss of data when a single server fails. When a server fails, another server fills the gap by providing a copy of the data that was on the failed server. When the failed server comes online again, it resumes its place in the cluster. Load balancing shares the computing load across the nodes of the cluster to improve the overall performance.

| Clustering of the runtime environment is currently supported on Red Hat JBoss EAP 7.2 only. Clustering of Business Central is currently a Technology Preview feature that is not yet intended for production use. |

2.1.4. Decision-authoring assets in Drools

Drools supports several assets that you can use to define business decisions for your decision service. Each decision-authoring asset has different advantages, and you might prefer to use one or a combination of multiple assets depending on your goals and needs.

The following table highlights the main decision-authoring assets supported in Drools projects to help you decide or confirm the best method for defining decisions in your decision service.

| Asset | Highlights | Authoring tools | Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|

Decision Model and Notation (DMN) models |

|

Business Central or other DMN-compliant editor |

|

Guided decision tables |

|

Business Central |

|

Spreadsheet decision tables |

|

Spreadsheet editor |

|

Guided rules |

|

Business Central |

|

Guided rule templates |

|

Business Central |

|

DRL rules |

|

Business Central or integrated development environment (IDE) |

|

Predictive Model Markup Language (PMML) models |

|

PMML or XML editor |

2.1.5. Project storage and build options with Drools

As you develop a Drools project, you need to be able to track the versions of your project with a version-controlled repository, manage your project assets in a stable environment, and build your project for testing and deployment. You can use Business Central for all of these tasks, or use a combination of Business Central and external tools and repositories. Drools supports Git repositories for project version control, Apache Maven for project management, and a variety of Maven-based, Java-based, or custom-tool-based build options.

The following options are the main methods for Drools project versioning, storage, and building:

| Versioning option | Description | Documentation |

|---|---|---|

Business Central Git VFS |

Business Central contains a built-in Git Virtual File System (VFS) that stores all processes, rules, and other artifacts that you create in the authoring environment. Git is a distributed version control system that implements revisions as commit objects. When you commit your changes into a repository, a new commit object in the Git repository is created. When you create a project in Business Central, the project is added to the Git repository connected to Business Central. |

NA |

External Git repository |

If you have Drools projects in Git repositories outside of Business Central, you can import them into Drools spaces and use Git hooks to synchronize the internal and external Git repositories. |

NA |

| Management option | Description | Documentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

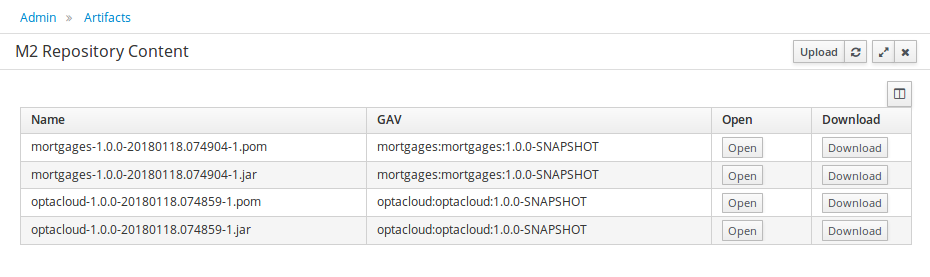

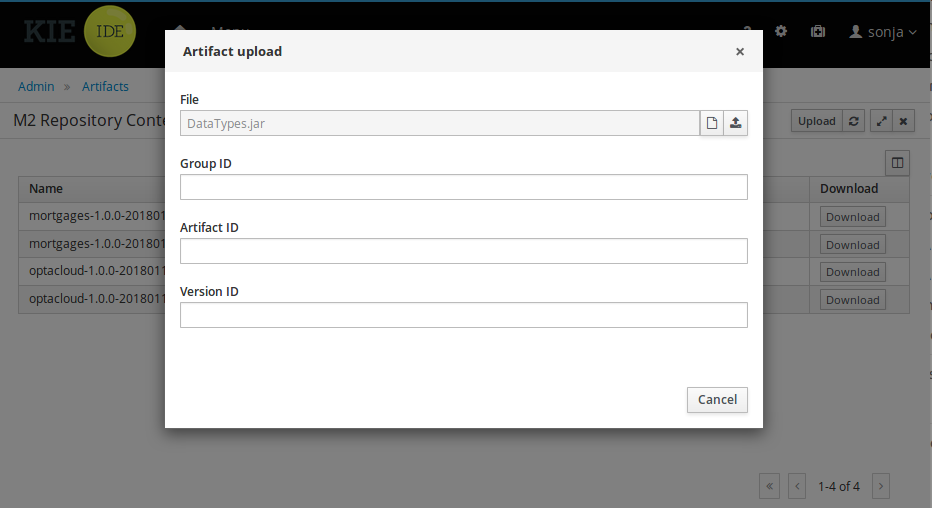

Business Central Maven repository |

Business Central contains a built-in Maven repository that organizes and builds project assets that you create in the authoring environment. Maven is a distributed build-automation tool that uses repositories to store Java libraries, plug-ins, and other build artifacts. When building projects and archetypes, Maven dynamically retrieves Java libraries and Maven plug-ins from local or remote repositories to promote shared dependencies across projects.

|

|||

External Maven repository |

If you have Drools projects in an external Maven repository, such as Nexus or Artifactory, you can create a |

| Build option | Description | Documentation |

|---|---|---|

Business Central (KJAR) |

Business Central builds Drools projects stored in either the built-in Maven repository or a configured external Maven repository. Projects in Business Central are packaged automatically as knowledge JAR (KJAR) files with all components needed for deployment when you build the projects. |

|

Standalone Maven project (KJAR) |

If you have a standalone Drools Maven project outside of Business Central, you can edit the project |

|

Embedded Java application (KJAR) |

If you have an embedded Java application from which you want to build your Drools project, you can use a |

|

CI/CD tool (KJAR) |

If you use a tool for continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD), you can configure the tool set to integrate with your Drools Git repositories to build a specified project. Ensure that your projects are packaged and built as KJAR files to ensure optimal deployment. |

NA |

2.1.6. Project deployment options with Drools

After you develop, test, and build your Drools project, you can deploy the project to begin using the business assets you have created. You can deploy a Drools project to a configured KIE Server, to an embedded Java application, or into a Red Hat OpenShift Container Platform environment for an enhanced containerized implementation.

The following options are the main methods for Drools project deployment:

| Deployment option | Description | Documentation |

|---|---|---|

Deployment to KIE Server |

KIE Server is the server provided with Drools that runs the decision services, process applications, and other deployable assets from a packaged and deployed Drools project (KJAR file). These services are consumed at run time through an instantiated KIE container, or deployment unit. You can deploy and maintain deployment units in KIE Server using Business Central or using a headless Drools controller with its associated REST API (considered a managed KIE Server instance). You can also deploy and maintain deployment units using the KIE Server REST API or Java client API from a standalone Maven project, an embedded Java application, or other custom environment (considered an unmanaged KIE Server instance). |

|

Deployment to an embedded Java application |

If you want to deploy Drools projects to your own Java virtual machine (JVM) environment, microservice, or application server, you can bundle the application resources in the project WAR files to create a deployment unit similar to a KIE container. You can also use the core KIE APIs (not KIE Server APIs) to configure a KIE scanner to periodically update KIE containers. |

2.1.7. Asset execution options with Drools

After you build and deploy your Drools project to KIE Server or other environment, you can execute the deployed assets for testing or for runtime consumption. You can also execute assets locally in addition to or instead of executing them after deployment.

The following options are the main methods for Drools asset execution:

| Execution option | Description | Documentation |

|---|---|---|

Execution in KIE Server |

If you deployed Drools project assets to KIE Server, you can use the KIE Server REST API or Java client API to execute and interact with the deployed assets. You can also use Business Central or the headless Drools controller outside of Business Central to manage the configurations and KIE containers in the KIE Server instances associated with your deployed assets. |

|

Execution in an embedded Java application |

If you deployed Drools project assets in your own Java virtual machine (JVM) environment, microservice, or application server, you can use custom APIs or application interactions with core KIE APIs (not KIE Server APIs) to execute assets in the embedded engine. |

|

Execution in a local environment for extended testing |

As part of your development cycle, you can execute assets locally to ensure that the assets you have created in Drools function as intended. You can use local execution in addition to or instead of executing assets after deployment. |

|

Smart Router (KIE Server router)

Depending on your deployment and execution environment, you can use a Smart Router to aggregate multiple independent KIE Server instances as though they are a single server. Smart Router is a single endpoint that can receive calls from client applications to any of your services and route each call automatically to the KIE Server that runs the service. For more information about Smart Router, see KIE Server router. |

2.1.8. Example decision management architectures with Drools

The following scenarios illustrate common variations of Drools installation, asset authoring, project storage, project deployment, and asset execution in a decision management architecture. Each section summarizes the methods and tools used and the advantages for the given architecture. The examples are basic and are only a few of the many combinations you might consider, depending on your specific goals and needs with Drools.

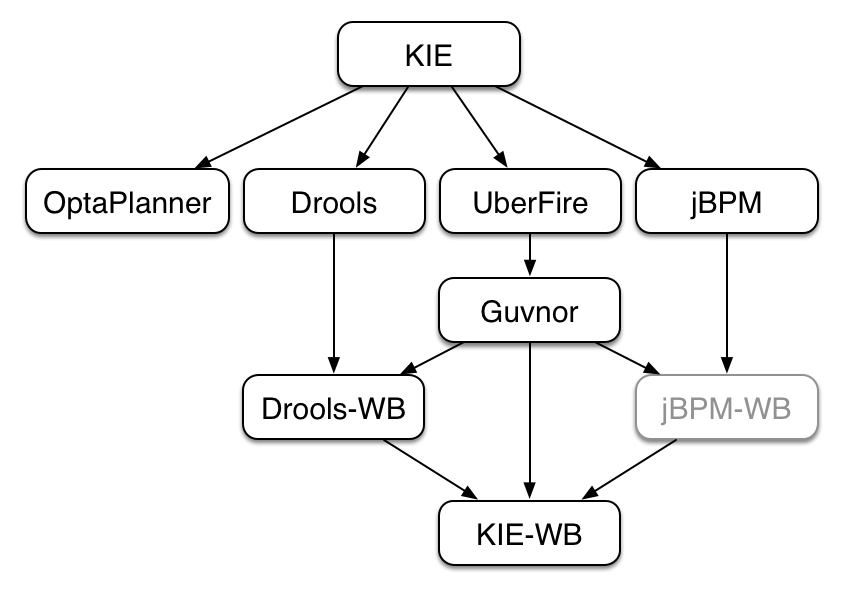

- Drools on Wildfly with Business Central and KIE Server

-

-

Installation environment: Drools on Wildfly

-

Project storage and build environment: External Git repository for project versioning synchronized with the Business Central Git repository using Git hooks, and external Maven repository for project management and building configured with KIE Server

-

Asset-authoring tool: Business Central

-

Main asset types: Decision Model and Notation (DMN) models for decisions

-

Project deployment and execution environment: KIE Server

-

Scenario advantages:

-

Stable implementation of Drools in an on-premise development environment

-

Access to the repositories, assets, asset designers, and project build options in Business Central

-

Standardized asset-authoring approach using DMN for optimal integration and stability

-

Access to KIE Server functionality and KIE APIs for asset deployment and execution

-

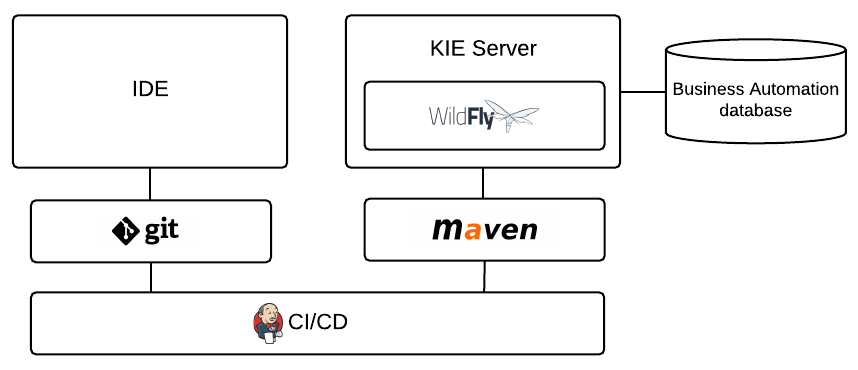

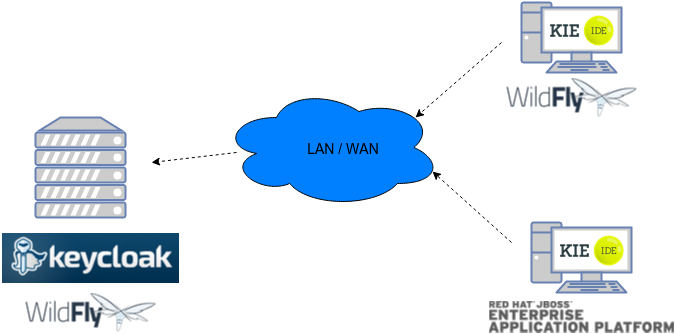

Figure 2. Drools on Wildfly with Business Central and KIE Server

Figure 2. Drools on Wildfly with Business Central and KIE Server -

- Drools on Wildfly with an IDE and KIE Server

-

-

Installation environment: Drools on Wildfly

-

Project storage and build environment: External Git repository for project versioning (not synchronized with Business Central) and external Maven repository for project management and building configured with KIE Server

-

Asset-authoring tools: Integrated development environment (IDE), such as Eclipse, and a spreadsheet editor or a Decision Model and Notation (DMN) modeling tool for other decision formats

-

Main asset types: Drools Rule Language (DRL) rules, spreadsheet decision tables, and Decision Model and Notation (DMN) models for decisions

-

Project deployment and execution environment: KIE Server

-

Scenario advantages:

-

Flexible implementation of Drools in an on-premise development environment

-

Ability to define business assets using an external IDE and other asset-authoring tools of your choice

-

Access to KIE Server functionality and KIE APIs for asset deployment and execution

-

Figure 3. Drools on Wildfly with an IDE and KIE Server

Figure 3. Drools on Wildfly with an IDE and KIE Server -

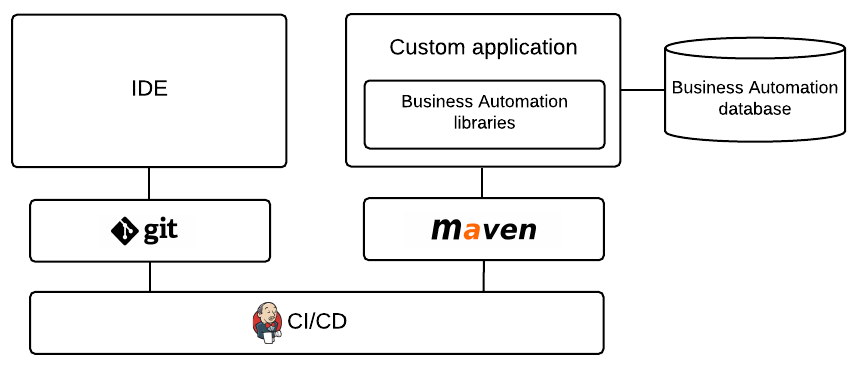

- Drools with an IDE and an embedded Java application

-

-

Installation environment: Drools libraries embedded within a custom application

-

Project storage and build environment: External Git repository for project versioning (not synchronized with Business Central) and external Maven repository for project management and building configured with your embedded Java application (not configured with KIE Server)

-

Asset-authoring tools: Integrated development environment (IDE), such as Eclipse, and a spreadsheet editor or a Decision Model and Notation (DMN) modeling tool for other decision formats

-

Main asset types: Drools Rule Language (DRL) rules, spreadsheet decision tables, and Decision Model and Notation (DMN) models for decisions

-

Project deployment and execution environment: Embedded Java application, such as in a Java virtual machine (JVM) environment, microservice, or custom application server

-

Scenario advantages:

-

Custom implementation of Drools in an on-premise development environment with an embedded Java application

-

Ability to define business assets using an external IDE and other asset-authoring tools of your choice

-

Use of custom APIs to interact with core KIE APIs (not KIE Server APIs) and to execute assets in the embedded engine

-

Figure 4. Drools with an IDE and an embedded Java application

Figure 4. Drools with an IDE and an embedded Java application -

2.2. Build, Deploy, Utilize and Run

2.2.1. Introduction

6.0 introduces a new configuration and convention approach to building KIE bases, instead of using the programmatic builder approach in 5.x. The builder is still available to fall back on, as it’s used for the tooling integration.

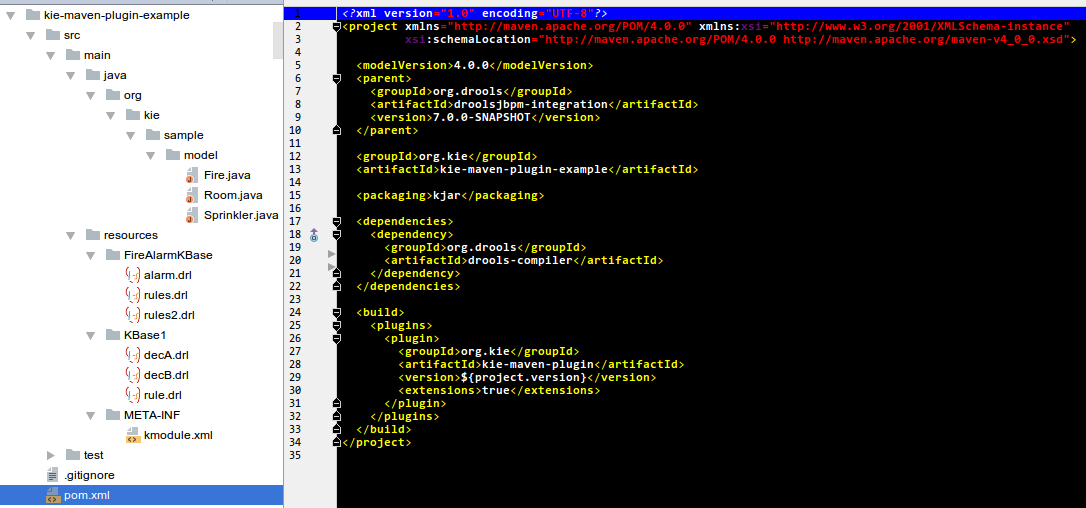

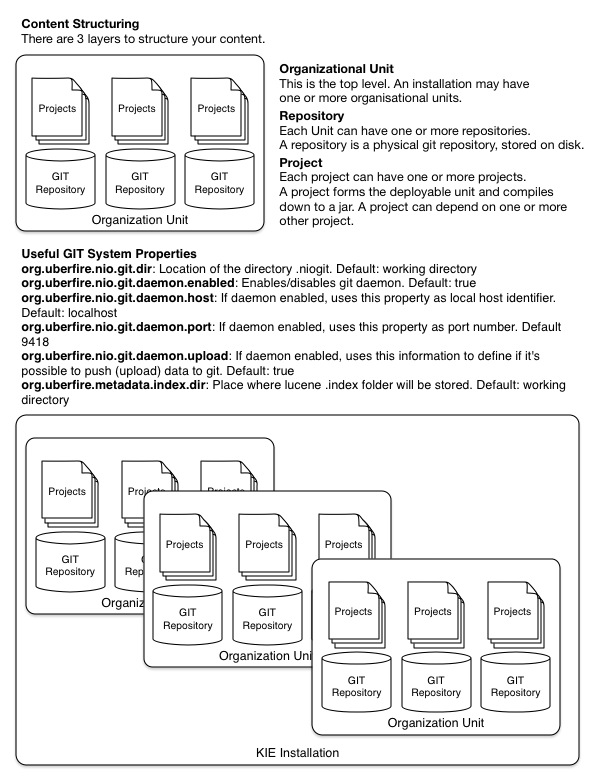

Building now uses Maven, and aligns with Maven practices. A KIE project or module is simply a Maven Java project or module; with an additional metadata file META-INF/kmodule.xml. The kmodule.xml file is the descriptor that selects resources to KIE bases and configures those KIE bases and sessions. There is also alternative XML support via Spring and OSGi BluePrints.

While standard Maven can build and package KIE resources, it will not provide validation at build time. There is a Maven plugin which is recommended to use to get build time validation. The plugin also generates many classes, making the runtime loading faster too.

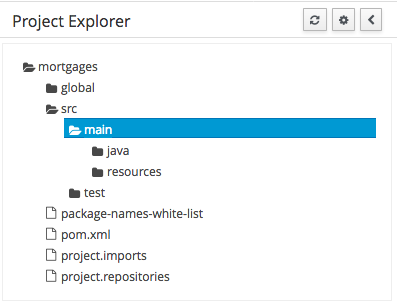

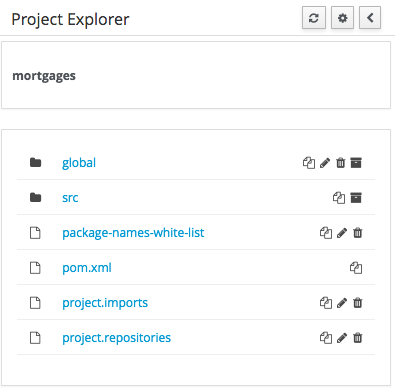

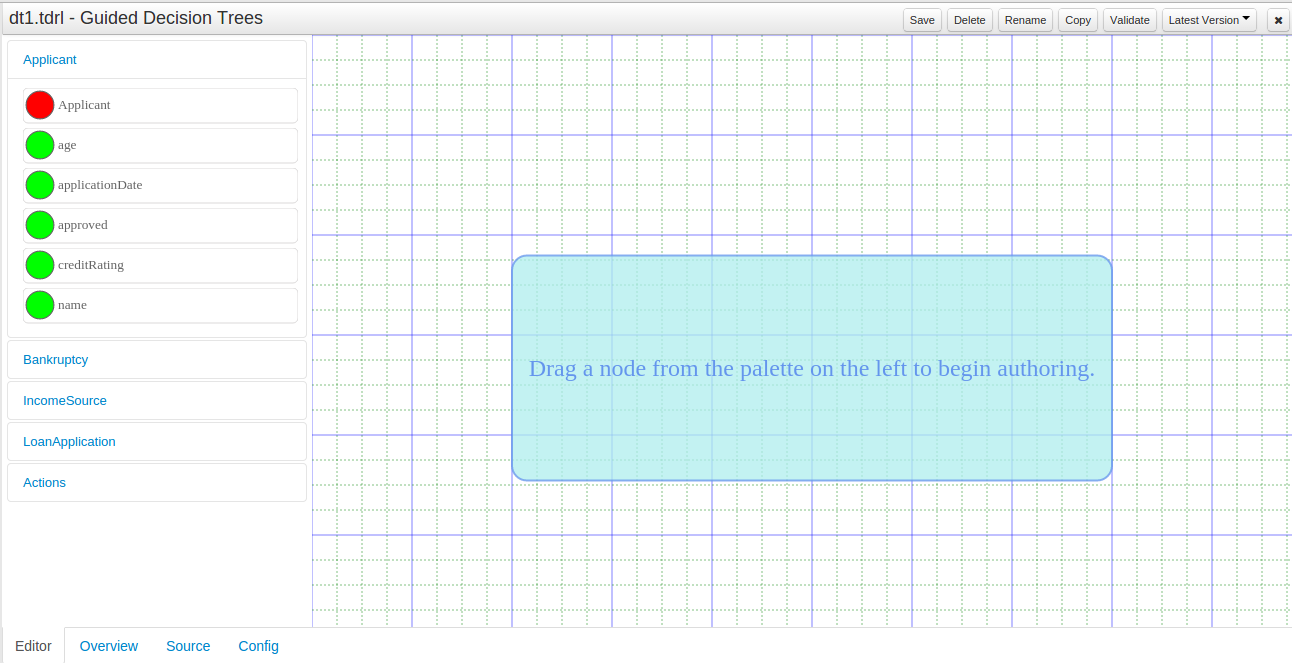

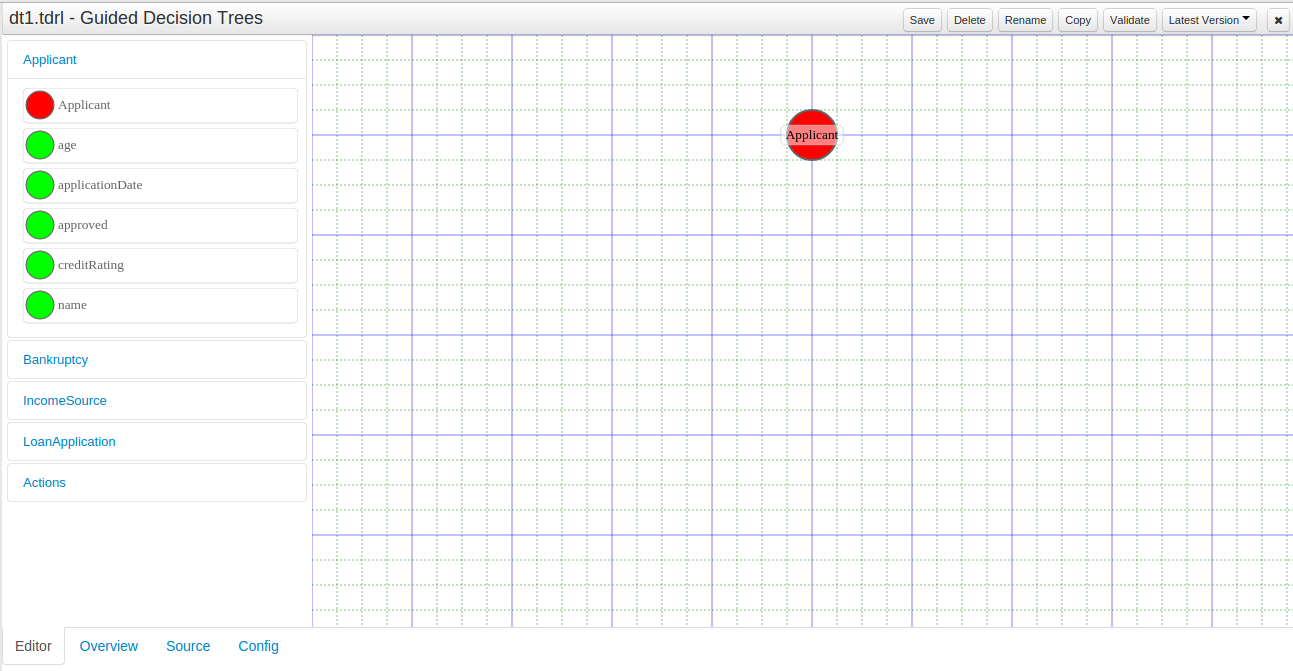

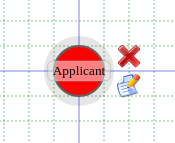

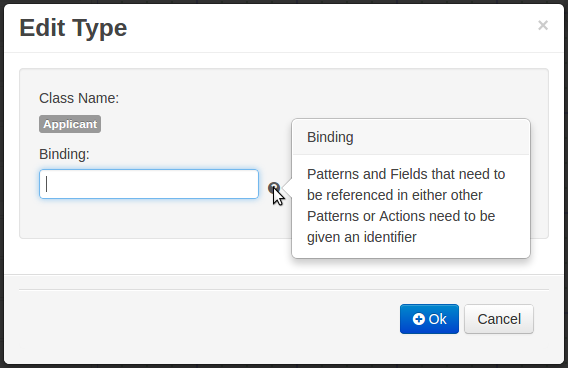

The example project layout and Maven POM descriptor is illustrated in the screenshot

KIE uses defaults to minimise the amount of configuration. With an empty kmodule.xml being the simplest configuration. There must always be a kmodule.xml file, even if empty, as it’s used for discovery of the JAR and its contents.

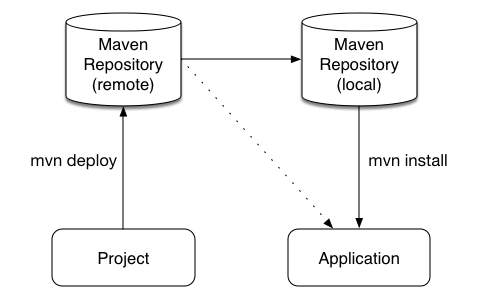

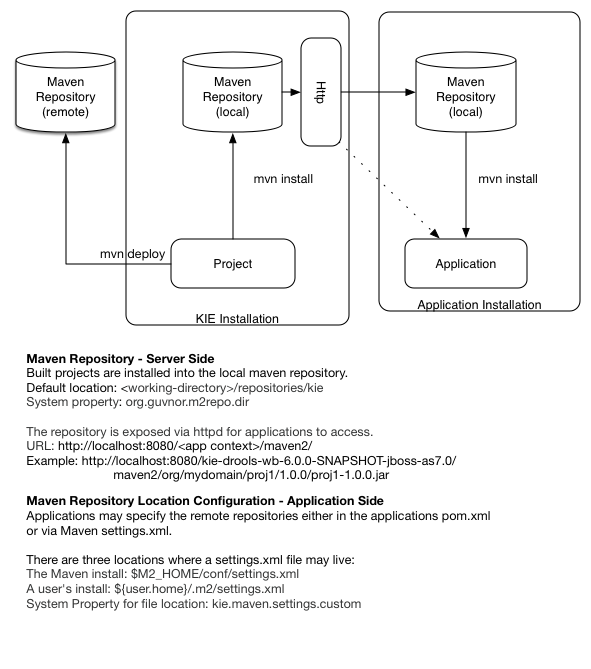

Maven can either 'mvn install' to deploy a KieModule to the local machine, where all other applications on the local machine use it. Or it can 'mvn deploy' to push the KieModule to a remote Maven repository. Building the Application will pull in the KieModule and populate the local Maven repository in the process.

JARs can be deployed in one of two ways. Either added to the classpath, like any other JAR in a Maven dependency listing, or they can be dynamically loaded at runtime. KIE will scan the classpath to find all the JARs with a kmodule.xml in it. Each found JAR is represented by the KieModule interface. The terms classpath KieModule and dynamic KieModule are used to refer to the two loading approaches. While dynamic modules supports side by side versioning, classpath modules do not. Further once a module is on the classpath, no other version may be loaded dynamically.

Detailed references for the API are included in the next sections, the impatient can jump straight to the examples section, which is fairly self-explanatory on the different use cases.

2.2.2. Building

2.2.2.1. Creating and building a Kie Project

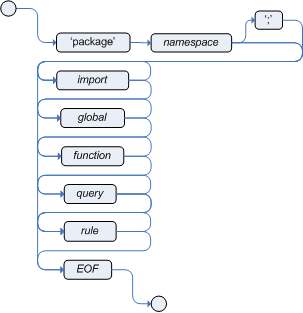

A Kie Project has the structure of a normal Maven project with the only peculiarity of including a kmodule.xml file defining in a declaratively way the KieBases and KieSessions that can be created from it.

This file has to be placed in the resources/META-INF folder of the Maven project while all the other Kie artifacts, such as DRL or a Excel files, must be stored in the resources folder or in any other subfolder under it.

Since meaningful defaults have been provided for all configuration aspects, the simplest kmodule.xml file can contain just an empty kmodule tag like the following:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<kmodule xmlns="http://www.drools.org/xsd/kmodule"/>In this way the kmodule will contain one single default KieBase.

All Kie assets stored under the resources folder, or any of its subfolders, will be compiled and added to it.

To trigger the building of these artifacts it is enough to create a KieContainer for them.

For this simple case it is enough to create a KieContainer that reads the files to be built from the classpath:

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

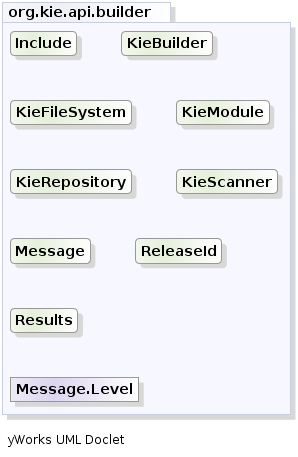

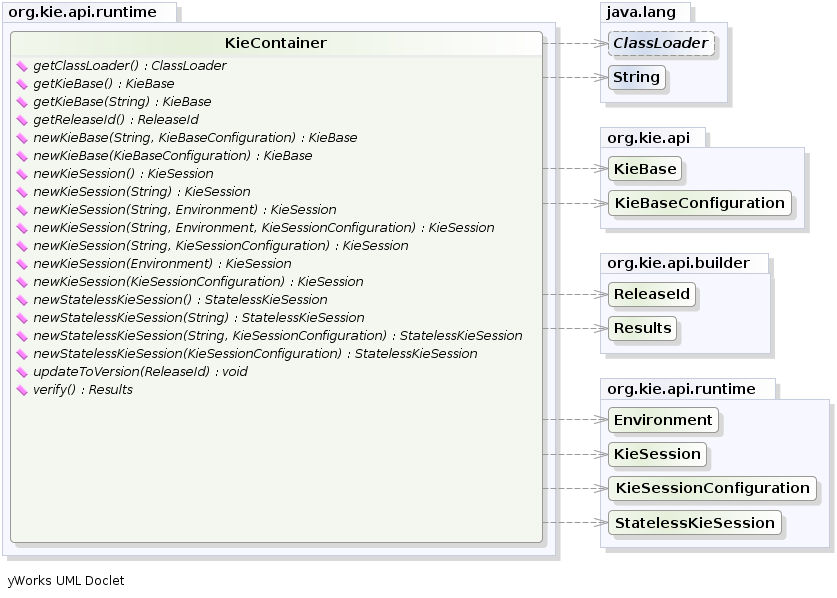

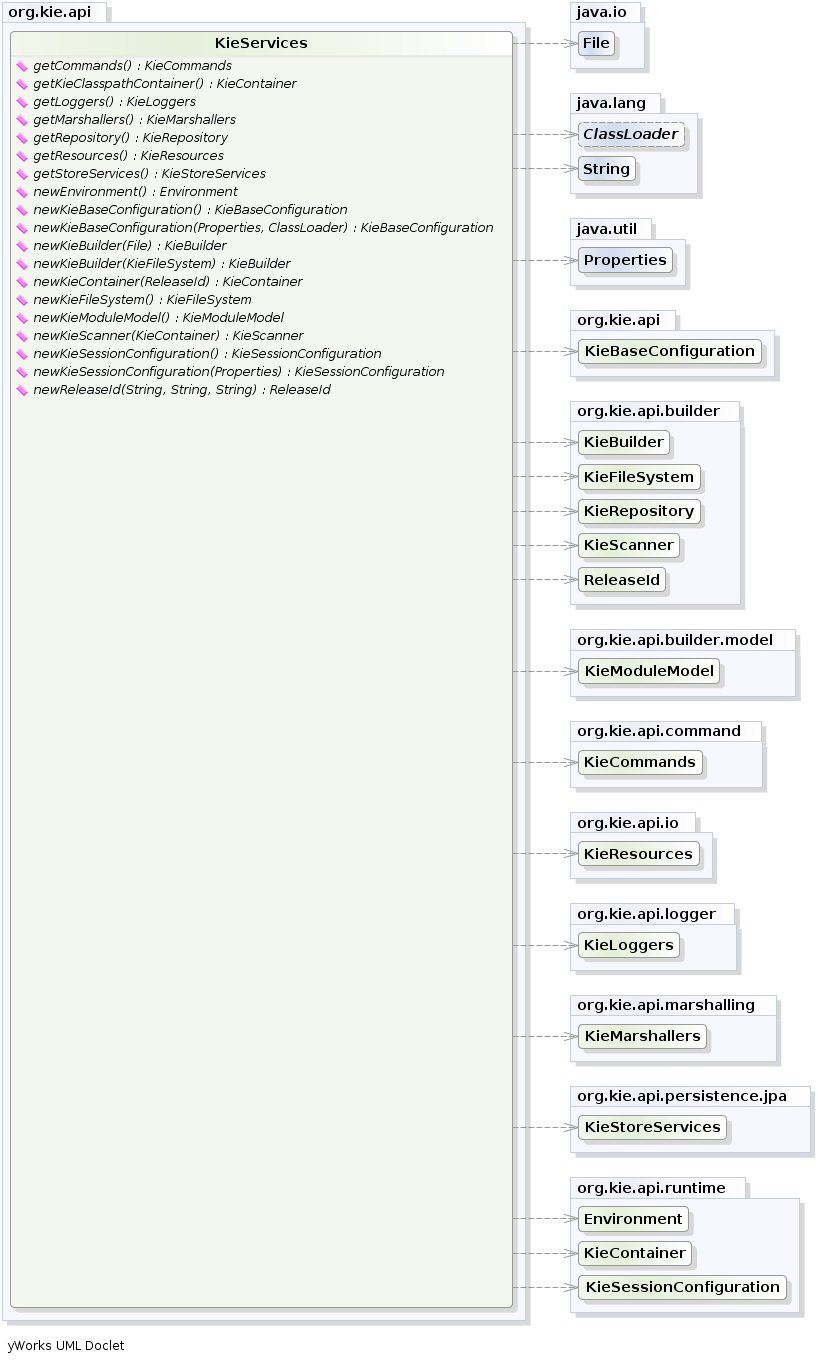

KieContainer kContainer = kieServices.getKieClasspathContainer();` KieServices` is the interface from where it possible to access all the Kie building and runtime facilities:

In this way all the Java sources and the Kie resources are compiled and deployed into the KieContainer which makes its contents available for use at runtime.

2.2.2.2. The kmodule.xml file

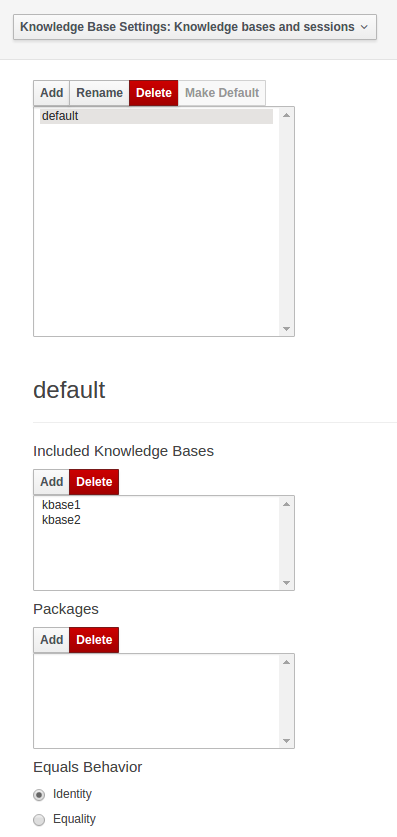

As explained in the former section, the kmodule.xml file is the place where it is possible to declaratively configure the KieBase(s) and KieSession(s) that can be created from a KIE project.

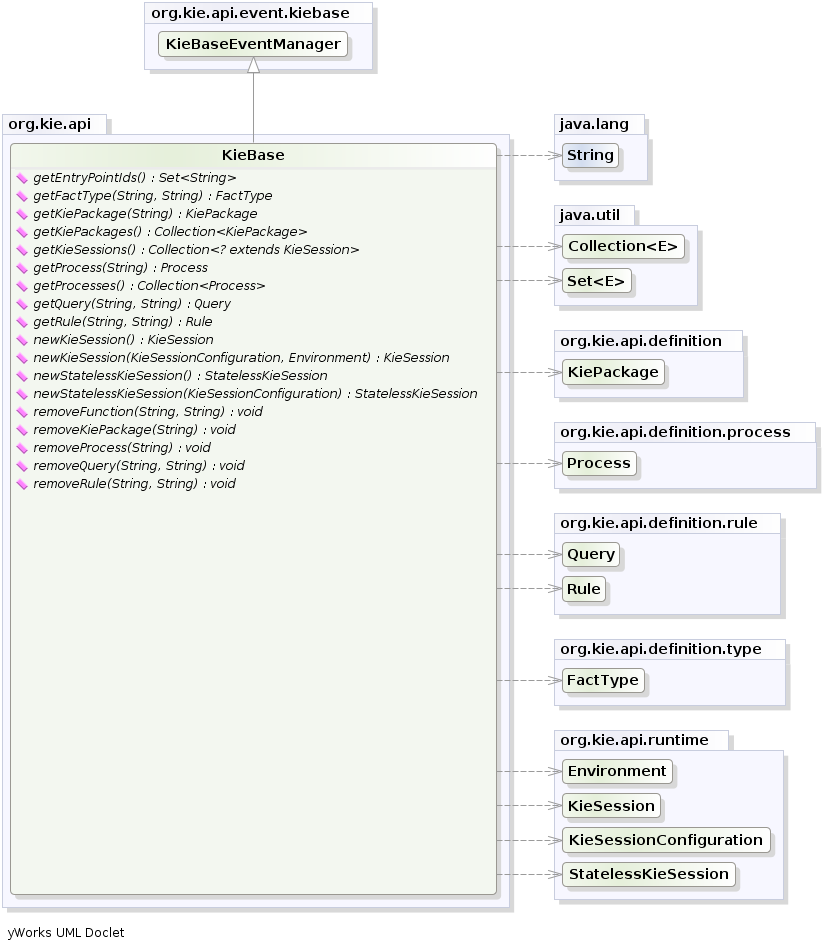

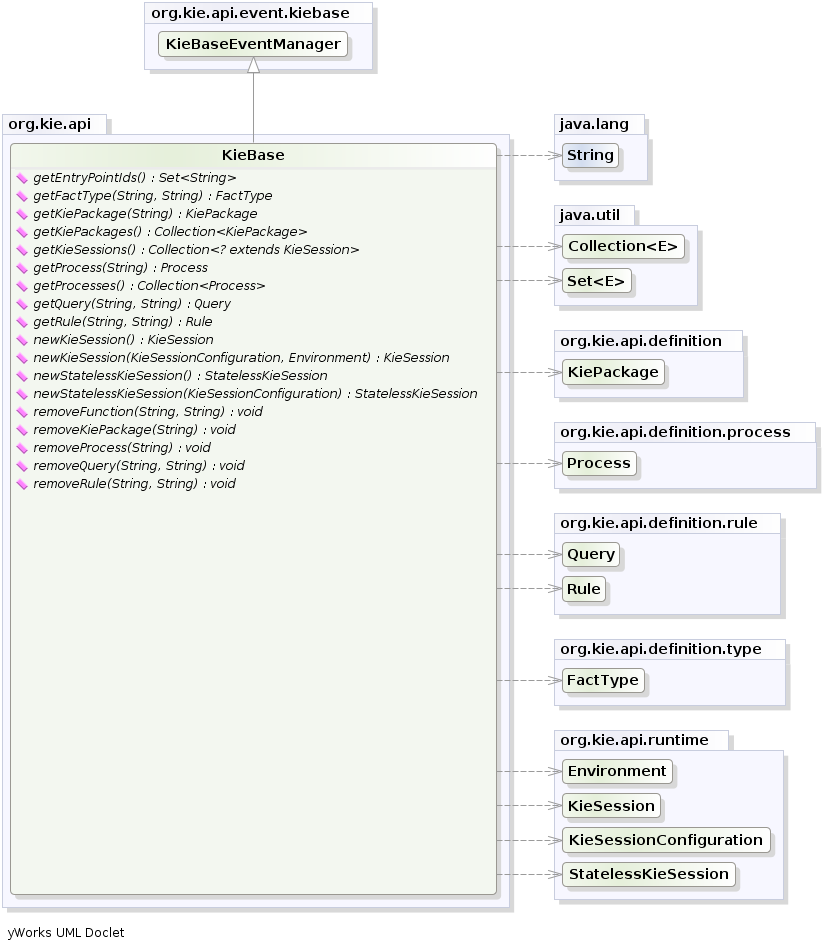

In particular a KieBase is a repository of all the application’s knowledge definitions.

It will contain rules, processes, functions, and type models.

The KieBase itself does not contain data; instead, sessions are created from the KieBase into which data can be inserted and from which process instances may be started.

Creating the KieBase can be heavy, whereas session creation is very light, so it is recommended that KieBase be cached where possible to allow for repeated session creation.

However end-users usually shouldn’t worry about it, because this caching mechanism is already automatically provided by the KieContainer.

Conversely the KieSession stores and executes on the runtime data.

It is created from the KieBase or more easily can be created directly from the KieContainer if it has been defined in the kmodule.xml file

The kmodule.xml allows to define and configure one or more KieBases and for each KieBase all the different KieSessions that can be created from it, as showed by the follwing example:

<kmodule xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns="http://www.drools.org/xsd/kmodule">

<configuration>

<property key="drools.evaluator.supersetOf" value="org.mycompany.SupersetOfEvaluatorDefinition"/>

</configuration>

<kbase name="KBase1" default="true" eventProcessingMode="cloud" equalsBehavior="equality" declarativeAgenda="enabled" packages="org.domain.pkg1">

<ksession name="KSession2_1" type="stateful" default="true"/>

<ksession name="KSession2_2" type="stateless" default="false" beliefSystem="jtms"/>

</kbase>

<kbase name="KBase2" default="false" eventProcessingMode="stream" equalsBehavior="equality" declarativeAgenda="enabled" packages="org.domain.pkg2, org.domain.pkg3" includes="KBase1">

<ksession name="KSession3_1" type="stateful" default="false" clockType="realtime">

<fileLogger file="drools.log" threaded="true" interval="10"/>

<workItemHandlers>

<workItemHandler name="name" type="org.domain.WorkItemHandler"/>

</workItemHandlers>

<calendars>

<calendar name="monday" type="org.domain.Monday"/>

</calendars>

<listeners>

<ruleRuntimeEventListener type="org.domain.RuleRuntimeListener"/>

<agendaEventListener type="org.domain.FirstAgendaListener"/>

<agendaEventListener type="org.domain.SecondAgendaListener"/>

<processEventListener type="org.domain.ProcessListener"/>

</listeners>

</ksession>

</kbase>

</kmodule>Here the

tag contains a list of key-value pairs that are the optional properties used to configure the KieBases building process.

For instance this sample kmodule.xml file defines an additional custom operator named supersetOf and implemented by the org.mycompany.SupersetOfEvaluatorDefinition class.

After this 2 KieBases have been defined and it is possible to instance 2 different types of KieSessions from the first one, while only one from the second.

A list of the attributes that can be defined on the kbase tag, together with their meaning and default values follows:

| Attribute name | Default value | Admitted values | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

name |

none |

any |

The name with which retrieve this KieBase from the KieContainer. This is the only mandatory attribute. |

includes |

none |

any comma separated list |

A comma separated list of other KieBases contained in this kmodule. The artifacts of all these KieBases will be also included in this one. |

packages |

all |

any comma separated list |

By default all the Drools artifacts under the resources folder, at any level, are included into the KieBase. This attribute allows to limit the artifacts that will be compiled in this KieBase to only the ones belonging to the list of packages. |

default |

false |

true, false |

Defines if this KieBase is the default one for this module, so it can be created from the KieContainer without passing any name to it. There can be at most one default KieBase in each module. |

equalsBehavior |

identity |

identity, equality |

Defines the behavior of Drools when a new fact is inserted into the Working Memory. With identity it always create a new FactHandle unless the same object isn’t already present in the Working Memory, while with equality only if the newly inserted object is not equal (according to its equal method) to an already existing fact. |

eventProcessingMode |

cloud |

cloud, stream |

When compiled in cloud mode the KieBase treats events as normal facts, while in stream mode allow temporal reasoning on them. |

declarativeAgenda |

disabled |

disabled, enabled |

Defines if the Declarative Agenda is enabled or not. |

Similarly all attributes of the ksession tag (except of course the name) have meaningful default. They are listed and described in the following table:

| Attribute name | Default value | Admitted values | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

name |

none |

any |

Unique name of this KieSession. Used to fetch the KieSession from the KieContainer. This is the only mandatory attribute. |

type |

stateful |

stateful, stateless |

A stateful session allows to iteratively work with the Working Memory, while a stateless one is a one-off execution of a Working Memory with a provided data set. |

default |

false |

true, false |

Defines if this KieSession is the default one for this module, so it can be created from the KieContainer without passing any name to it. In each module there can be at most one default KieSession for each type. |

clockType |

realtime |

realtime, pseudo |

Defines if events timestamps are determined by the system clock or by a psuedo clock controlled by the application. This clock is specially useful for unit testing temporal rules. |

beliefSystem |

simple |

simple, jtms, defeasible |

Defines the type of belief system used by the KieSession. |

As outlined in the former kmodule.xml sample, it is also possible to declaratively create on each KieSession a file (or a console) logger, one or more WorkItemHandlers and Calendars plus some listeners that can be of 3 different types: ruleRuntimeEventListener, agendaEventListener and processEventListener

Having defined a kmodule.xml like the one in the former sample, it is now possible to simply retrieve the KieBases and KieSessions from the KieContainer using their names.

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

KieContainer kContainer = kieServices.getKieClasspathContainer();

KieBase kBase1 = kContainer.getKieBase("KBase1");

KieSession kieSession1 = kContainer.newKieSession("KSession2_1");

StatelessKieSession kieSession2 = kContainer.newStatelessKieSession("KSession2_2");It has to be noted that since KSession2_1 and KSession2_2 are of 2 different types (the first is stateful, while the second is stateless) it is necessary to invoke 2 different methods on the KieContainer according to their declared type.

If the type of the KieSession requested to the KieContainer doesn’t correspond with the one declared in the kmodule.xml file the KieContainer will throw a RuntimeException.

Also since a KieBase and a KieSession have been flagged as default is it possible to get them from the KieContainer without passing any name.

KieContainer kContainer = ...

KieBase kBase1 = kContainer.getKieBase(); // returns KBase1

KieSession kieSession1 = kContainer.newKieSession(); // returns KSession2_1Since a Kie project is also a Maven project the groupId, artifactId and version declared in the pom.xml file are used to generate a ReleaseId that uniquely identifies this project inside your application.

This allows creation of a new KieContainer from the project by simply passing its ReleaseId to the KieServices.

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

ReleaseId releaseId = kieServices.newReleaseId( "org.acme", "myartifact", "1.0" );

KieContainer kieContainer = kieServices.newKieContainer( releaseId );2.2.2.3. Building with Maven

The KIE plugin for Maven ensures that artifact resources are validated and pre-compiled, it is recommended that this is used at all times.

To use the plugin simply add it to the build section of the Maven pom.xml and activate it by using packaging kjar.

<packaging>kjar</packaging>

...

<build>

<plugins>

<plugin>

<groupId>org.kie</groupId>

<artifactId>kie-maven-plugin</artifactId>

<version>7.23.0.Final</version>

<extensions>true</extensions>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>The plugin comes with support for all the Drools/jBPM knowledge resources.

However, in case you are using specific KIE annotations in your Java classes, like for example @kie.api.Position, you will need to add compile time dependency on kie-api into your project.

We recommend to use the provided scope for all the additional KIE dependencies.

That way the kjar stays as lightweight as possible, and not dependant on any particular KIE version.

Building a KIE module without the Maven plugin will copy all the resources, as is, into the resulting JAR. When that JAR is loaded by the runtime, it will attempt to build all the resources then. If there are compilation issues it will return a null KieContainer. It also pushes the compilation overhead to the runtime. In general this is not recommended, and the Maven plugin should always be used.

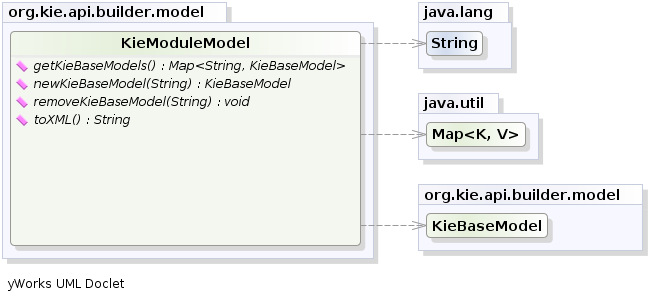

2.2.2.4. Defining a KieModule programmatically

It is also possible to define the KieBases and KieSessions belonging to a KieModule programmatically instead of the declarative definition in the kmodule.xml file.

The same programmatic API also allows in explicitly adding the file containing the Kie artifacts instead of automatically read them from the resources folder of your project.

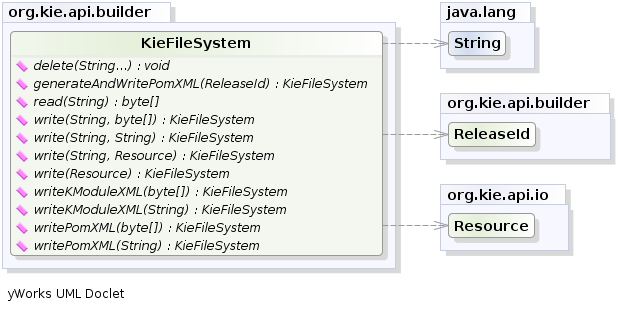

To do that it is necessary to create a KieFileSystem, a sort of virtual file system, and add all the resources contained in your project to it.

Like all other Kie core components you can obtain an instance of the KieFileSystem from the KieServices.

The kmodule.xml configuration file must be added to the filesystem.

This is a mandatory step.

Kie also provides a convenient fluent API, implemented by the KieModuleModel, to programmatically create this file.

To do this in practice it is necessary to create a KieModuleModel from the KieServices, configure it with the desired KieBases and KieSessions, convert it in XML and add the XML to the KieFileSystem.

This process is shown by the following example:

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

KieModuleModel kieModuleModel = kieServices.newKieModuleModel();

KieBaseModel kieBaseModel1 = kieModuleModel.newKieBaseModel( "KBase1 ")

.setDefault( true )

.setEqualsBehavior( EqualityBehaviorOption.EQUALITY )

.setEventProcessingMode( EventProcessingOption.STREAM );

KieSessionModel ksessionModel1 = kieBaseModel1.newKieSessionModel( "KSession1" )

.setDefault( true )

.setType( KieSessionModel.KieSessionType.STATEFUL )

.setClockType( ClockTypeOption.get("realtime") );

KieFileSystem kfs = kieServices.newKieFileSystem();

kfs.writeKModuleXML(kieModuleModel.toXML());At this point it is also necessary to add to the KieFileSystem, through its fluent API, all others Kie artifacts composing your project.

These artifacts have to be added in the same position of a corresponding usual Maven project.

KieFileSystem kfs = ...

kfs.write( "src/main/resources/KBase1/ruleSet1.drl", stringContainingAValidDRL )

.write( "src/main/resources/dtable.xls",

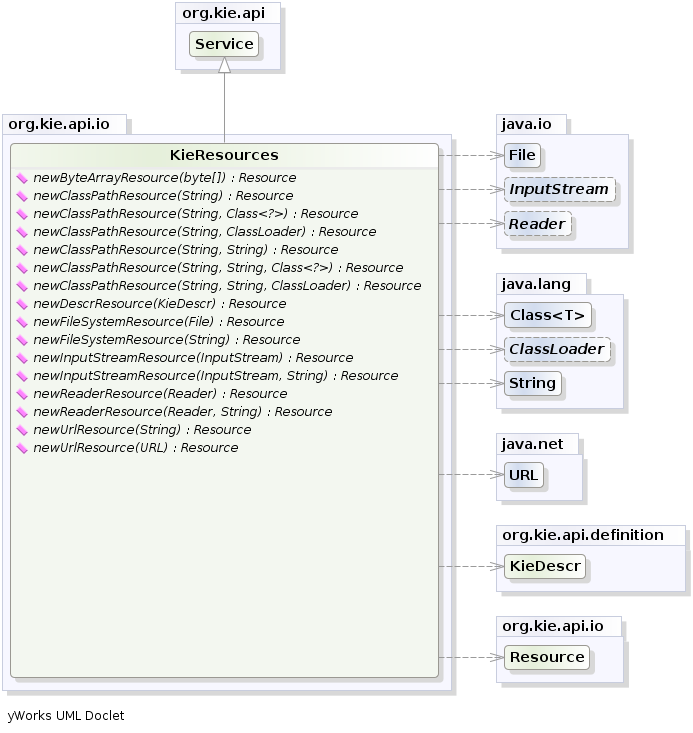

kieServices.getResources().newInputStreamResource( dtableFileStream ) );This example shows that it is possible to add the Kie artifacts both as plain Strings and as Resources.

In the latter case the Resources can be created by the KieResources factory, also provided by the KieServices.

The KieResources provides many convenient factory methods to convert an InputStream, a URL, a File, or a String representing a path of your file system to a Resource that can be managed by the KieFileSystem.

Normally the type of a Resource can be inferred from the extension of the name used to add it to the KieFileSystem.

However it also possible to not follow the Kie conventions about file extensions and explicitly assign a specific ResourceType to a Resource as shown below:

KieFileSystem kfs = ...

kfs.write( "src/main/resources/myDrl.txt",

kieServices.getResources().newInputStreamResource( drlStream )

.setResourceType(ResourceType.DRL) );Add all the resources to the KieFileSystem and build it by passing the KieFileSystem to a KieBuilder

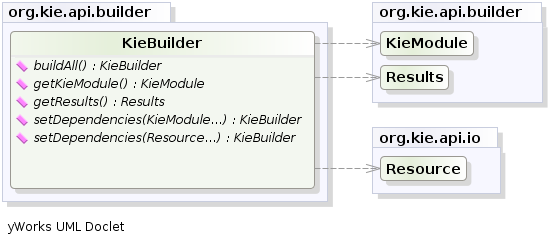

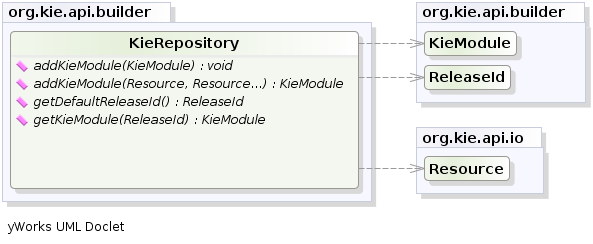

When the contents of a KieFileSystem are successfully built, the resulting KieModule is automatically added to the KieRepository.

The KieRepository is a singleton acting as a repository for all the available KieModules.

After this it is possible to create through the KieServices a new KieContainer for that KieModule using its ReleaseId.

However, since in this case the KieFileSystem doesn’t contain any pom.xml file (it is possible to add one using the KieFileSystem.writePomXML method), Kie cannot determine the ReleaseId of the KieModule and assign to it a default one.

This default ReleaseId can be obtained from the KieRepository and used to identify the KieModule inside the KieRepository itself.

The following example shows this whole process.

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

KieFileSystem kfs = ...

kieServices.newKieBuilder( kfs ).buildAll();

KieContainer kieContainer = kieServices.newKieContainer(kieServices.getRepository().getDefaultReleaseId());At this point it is possible to get KieBases and create new KieSessions from this KieContainer exactly in the same way as in the case of a KieContainer created directly from the classpath.

It is a best practice to check the compilation results.

The KieBuilder reports compilation results of 3 different severities: ERROR, WARNING and INFO.

An ERROR indicates that the compilation of the project failed and in the case no KieModule is produced and nothing is added to the KieRepository.

WARNING and INFO results can be ignored, but are available for inspection.

KieBuilder kieBuilder = kieServices.newKieBuilder( kfs ).buildAll();

assertEquals( 0, kieBuilder.getResults().getMessages( Message.Level.ERROR ).size() );2.2.2.5. Changing the Default Build Result Severity

In some cases, it is possible to change the default severity of a type of build result. For instance, when a new rule with the same name of an existing rule is added to a package, the default behavior is to replace the old rule by the new rule and report it as an INFO. This is probably ideal for most use cases, but in some deployments the user might want to prevent the rule update and report it as an error.

Changing the default severity for a result type, configured like any other option in Drools, can be done by API calls, system properties or configuration files. As of this version, Drools supports configurable result severity for rule updates and function updates. To configure it using system properties or configuration files, the user has to use the following properties:

// sets the severity of rule updates

drools.kbuilder.severity.duplicateRule = <INFO|WARNING|ERROR>

// sets the severity of function updates

drools.kbuilder.severity.duplicateFunction = <INFO|WARNING|ERROR>2.2.2.6. Building and running Drools in a fat jar

Many modules of Drools (e.g. drools-core, drools-compiler) have a file named kie.conf containing the names of the classes implementing the services

provided by the corresponding module. When running Drools in a fat JAR, for example created by the Maven Shade Plugin, those various kie.conf files

need to be merged, otherwise , the fat JAR will contain only 1 kie.conf from a single dependency, resulting into errors. You can merge resources in

the Maven Shade Plugin using transformers, like this:

<transformer implementation="org.apache.maven.plugins.shade.resource.AppendingTransformer">

<resource>META-INF/kie.conf</resource>

</transformer>For instance this is required when running Drools in a Vert.x application. In this case the Maven Shade Plugin can be configured as it follows:

<plugin>

<groupId>org.apache.maven.plugins</groupId>

<artifactId>maven-shade-plugin</artifactId>

<version>3.1.0</version>

<executions>

<execution>

<phase>package</phase>

<goals>

<goal>shade</goal>

</goals>

<configuration>

<transformers>

<transformer implementation="org.apache.maven.plugins.shade.resource.ManifestResourceTransformer">

<manifestEntries>

<Main-Class>io.vertx.core.Launcher</Main-Class>

<Main-Verticle>${main.verticle}</Main-Verticle>

</manifestEntries>

</transformer>

<transformer implementation="org.apache.maven.plugins.shade.resource.AppendingTransformer">

<resource>META-INF/services/io.vertx.core.spi.VerticleFactory</resource>

</transformer>

<transformer implementation="org.apache.maven.plugins.shade.resource.AppendingTransformer">

<resource>META-INF/kie.conf</resource>

</transformer>

</transformers>

<artifactSet>

</artifactSet>

<outputFile>${project.build.directory}/${project.artifactId}-${project.version}-fat.jar</outputFile>

</configuration>

</execution>

</executions>

</plugin>2.2.3. Deploying

2.2.3.1. KieBase

The KieBase is a repository of all the application’s knowledge definitions.

It will contain rules, processes, functions, and type models.

The KieBase itself does not contain data; instead, sessions are created from the KieBase into which data can be inserted and from which process instances may be started.

The KieBase can be obtained from the KieContainer containing the KieModule where the KieBase has been defined.

Sometimes, for instance in a OSGi environment, the KieBase needs to resolve types that are not in the default class loader.

In this case it will be necessary to create a KieBaseConfiguration with an additional class loader and pass it to KieContainer when creating a new KieBase from it.

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

KieBaseConfiguration kbaseConf = kieServices.newKieBaseConfiguration( null, MyType.class.getClassLoader() );

KieBase kbase = kieContainer.newKieBase( kbaseConf );2.2.3.2. KieSessions and KieBase Modifications

KieSessions will be discussed in more detail in section "Running". The KieBase creates and returns KieSession objects, and it may optionally keep references to those.

When KieBase modifications occur those modifications are applied against the data in the sessions.

This reference is a weak reference and it is also optional, which is controlled by a boolean flag.

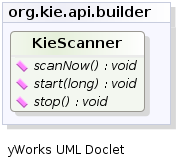

2.2.3.3. KieScanner

The KieScanner allows continuous monitoring of your Maven repository to check whether a new release of a Kie project has been installed.

A new release is deployed in the KieContainer wrapping that project.

The use of the KieScanner requires kie-ci.jar to be on the classpath.

A KieScanner can be registered on a KieContainer as in the following example.

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

ReleaseId releaseId = kieServices.newReleaseId( "org.acme", "myartifact", "1.0-SNAPSHOT" );

KieContainer kContainer = kieServices.newKieContainer( releaseId );

KieScanner kScanner = kieServices.newKieScanner( kContainer );

// Start the KieScanner polling the Maven repository every 10 seconds

kScanner.start( 10000L );In this example the KieScanner is configured to run with a fixed time interval, but it is also possible to run it on demand by invoking the scanNow() method on it.

If the KieScanner finds, in the Maven repository, an updated version of the Kie project used by that KieContainer it automatically downloads the new version and triggers an incremental build of the new project.

At this point, existing KieBases and KieSessions under the control of KieContainer will get automatically upgraded with it - specifically, those KieBases obtained with getKieBase() along with their related KieSessions, and any KieSession obtained directly with KieContainer.newKieSession() thus referencing the default KieBase.

Additionally, from this moment on, all the new KieBases and KieSessions created from that KieContainer will use the new project version.

Please notice however any existing KieBase which was obtained via newKieBase() before the KieScanner upgrade, and any of its related KieSessions, will not get automatically upgraded; this is because KieBases obtained via newKieBase() are not under the direct control of the KieContainer.

The KieScanner will only pickup changes to deployed jars if it is using a SNAPSHOT, version range, the LATEST, or the RELEASE setting.

Fixed versions will not automatically update at runtime.

In case you don’t want to install a maven repository, it is also possible to have a KieScanner that works

by simply fetching update from a folder of a plain file system. You can create such a KieScanner as simply as

KieServices kieServices = KieServices.Factory.get();

KieScanner kScanner = kieServices.newKieScanner( kContainer, "/myrepo/kjars" );where "/myrepo/kjars" will be the folder where the KieScanner will look for kjar updates. The jar files placed in this folder

have to follow the maven convention and then have to be a name in the form {artifactId}-{versionId}.jar

2.2.3.4. Maven Versions and Dependencies

Maven supports a number of mechanisms to manage versioning and dependencies within applications. Modules can be published with specific version numbers, or they can use the SNAPSHOT suffix. Dependencies can specify version ranges to consume, or take avantage of SNAPSHOT mechanism.

StackOverflow provides a very good description for this, which is reproduced below.

| Since Maven 3.x metaversions RELEASE and LATEST are no longer supported for the sake of reproducible builds. |

See the POM Syntax section of the Maven book for more details.

Here’s an example illustrating the various options. In the Maven repository, com.foo:my-foo has the following metadata:

<metadata>

<groupId>com.foo</groupId>

<artifactId>my-foo</artifactId>

<version>2.0.0</version>

<versioning>

<release>1.1.1</release>

<versions>

<version>1.0</version>

<version>1.0.1</version>

<version>1.1</version>

<version>1.1.1</version>

<version>2.0.0</version>

</versions>

<lastUpdated>20090722140000</lastUpdated>

</versioning>

</metadata>If a dependency on that artifact is required, you have the following options (other version ranges can be specified of course, just showing the relevant ones here): Declare an exact version (will always resolve to 1.0.1):

<version>[1.0.1]</version>Declare an explicit version (will always resolve to 1.0.1 unless a collision occurs, when Maven will select a matching version):

<version>1.0.1</version>Declare a version range for all 1.x (will currently resolve to 1.1.1):

<version>[1.0.0,2.0.0)</version>Declare an open-ended version range (will resolve to 2.0.0):

<version>[1.0.0,)</version>Declare the version as LATEST (will resolve to 2.0.0):

<version>LATEST</version>Declare the version as RELEASE (will resolve to 1.1.1):

<version>RELEASE</version>Note that by default your own deployments will update the "latest" entry in the Maven metadata, but to update the "release" entry, you need to activate the "release-profile" from the Maven super POM. You can do this with either "-Prelease-profile" or "-DperformRelease=true"

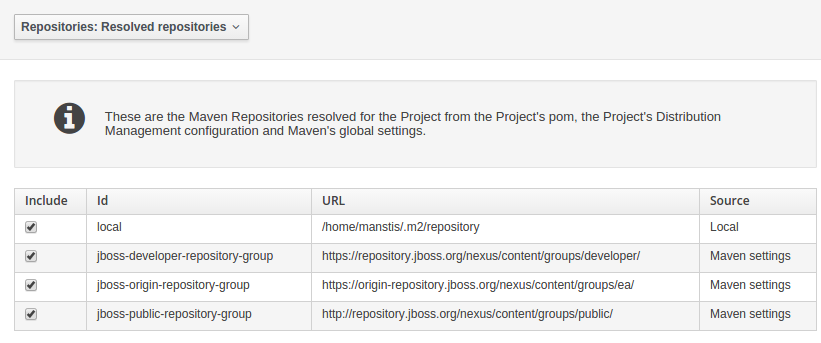

2.2.3.5. Settings.xml and Remote Repository Setup

The maven settings.xml is used to configure Maven execution. Detailed instructions can be found at the Maven website:

The settings.xml file can be located in 3 locations, the actual settings used is a merge of those 3 locations.

-

The Maven install:

$M2_HOME/conf/settings.xml -

A user’s install:

${user.home}/.m2/settings.xml -

Folder location specified by the system property

kie.maven.settings.custom

The settings.xml is used to specify the location of remote repositories. It is important that you activate the profile that specifies the remote repository, typically this can be done using "activeByDefault":

<profiles>

<profile>

<id>profile-1</id>

<activation>

<activeByDefault>true</activeByDefault>

</activation>

...

</profile>

</profiles>Maven provides detailed documentation on using multiple remote repositories:

2.2.4. Running

2.2.4.1. KieBase

The KieBase is a repository of all the application’s knowledge definitions.

It will contain rules, processes, functions, and type models.

The KieBase itself does not contain data; instead, sessions are created from the KieBase into which data can be inserted and from which process instances may be started.

The KieBase can be obtained from the KieContainer containing the KieModule where the KieBase has been defined.

KieBase kBase = kContainer.getKieBase();2.2.4.2. KieSession

The KieSession stores and executes on the runtime data.

It is created from the KieBase.

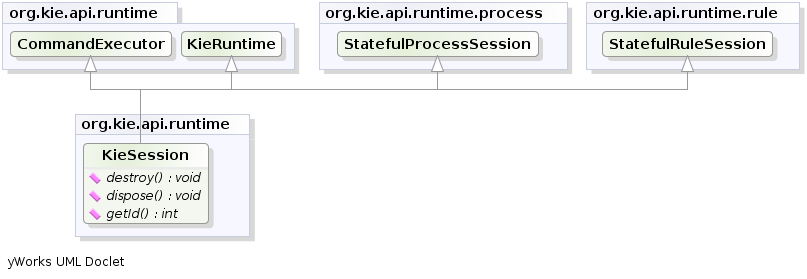

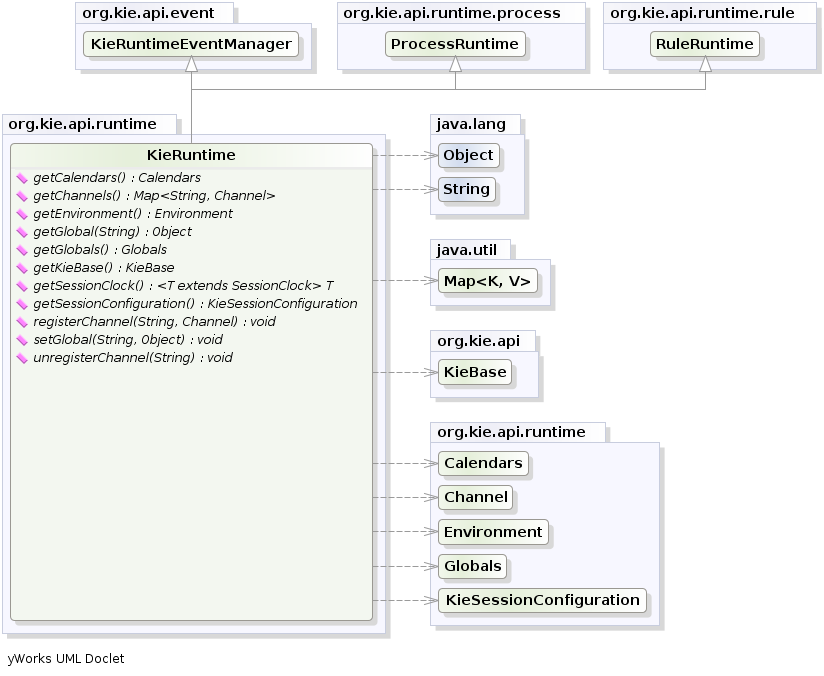

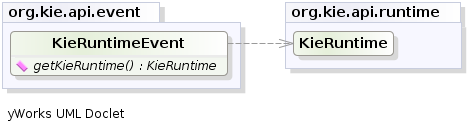

KieSession ksession = kbase.newKieSession();2.2.4.3. KieRuntime

KieRuntime

The KieRuntime provides methods that are applicable to both rules and processes, such as setting globals and registering channels.

("Exit point" is an obsolete synonym for "channel".)

Globals are named objects that are made visible to the Drools engine, but in a way that is fundamentally different from the one for facts: changes in the object backing a global do not trigger reevaluation of rules. Still, globals are useful for providing static information, as an object offering services that are used in the RHS of a rule, or as a means to return objects from the Drools engine. When you use a global on the LHS of a rule, make sure it is immutable, or, at least, don’t expect changes to have any effect on the behavior of your rules.

A global must be declared in a rules file, and then it needs to be backed up with a Java object.

global java.util.List listWith the KIE base now aware of the global identifier and its type, it is now possible to call ksession.setGlobal() with the global’s name and an object, for any session, to associate the object with the global.

Failure to declare the global type and identifier in DRL code will result in an exception being thrown from this call.

List list = new ArrayList();

ksession.setGlobal("list", list);Make sure to set any global before it is used in the evaluation of a rule.

Failure to do so results in a NullPointerException.

2.2.4.4. Event Model

The event package provides means to be notified of Drools engine events, including rules firing, objects being asserted, etc. This allows separation of logging and auditing activities from the main part of your application (and the rules).

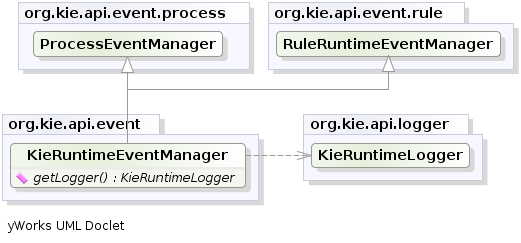

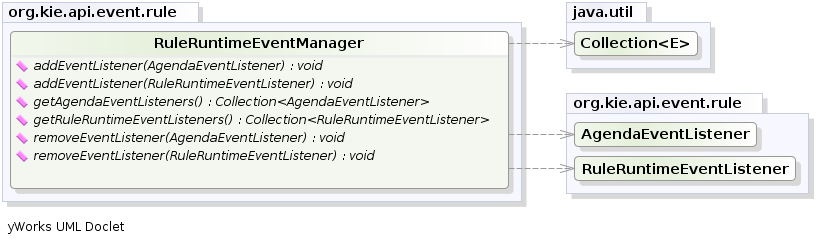

The KieRuntimeEventManager interface is implemented by the KieRuntime which provides two interfaces, RuleRuntimeEventManager and ProcessEventManager.

We will only cover the RuleRuntimeEventManager here.

The RuleRuntimeEventManager allows for listeners to be added and removed, so that events for the working memory and the agenda can be listened to.

The following code snippet shows how a simple agenda listener is declared and attached to a session. It will print matches after they have fired.

ksession.addEventListener( new DefaultAgendaEventListener() {

public void afterMatchFired(AfterMatchFiredEvent event) {

super.afterMatchFired( event );

System.out.println( event );

}

});Drools also provides DebugRuleRuntimeEventListener and DebugAgendaEventListener which implement each method with a debug print statement.

To print all Working Memory events, you add a listener like this:

ksession.addEventListener( new DebugRuleRuntimeEventListener() );All emitted events implement the KieRuntimeEvent interface which can be used to retrieve the actual KnowlegeRuntime the event originated from.

The events currently supported are:

-

MatchCreatedEvent

-

MatchCancelledEvent

-

BeforeMatchFiredEvent

-

AfterMatchFiredEvent

-

AgendaGroupPushedEvent

-

AgendaGroupPoppedEvent

-

ObjectInsertEvent

-

ObjectDeletedEvent

-

ObjectUpdatedEvent

-

ProcessCompletedEvent

-

ProcessNodeLeftEvent

-

ProcessNodeTriggeredEvent

-

ProcessStartEvent

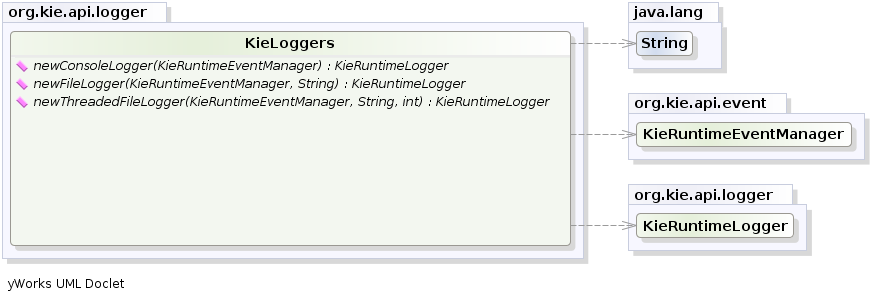

2.2.4.5. KieRuntimeLogger

The KieRuntimeLogger uses the comprehensive event system in Drools to create an audit log that can be used to log the execution of an application for later inspection, using tools such as the Eclipse audit viewer.

KieRuntimeLogger logger =

KieServices.Factory.get().getLoggers().newFileLogger(ksession, "logdir/mylogfile");

...

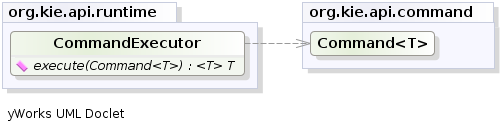

logger.close();2.2.4.6. Commands and the CommandExecutor

KIE has the concept of stateful or stateless sessions. Stateful sessions have already been covered, which use the standard KieRuntime, and can be worked with iteratively over time. Stateless is a one-off execution of a KieRuntime with a provided data set. It may return some results, with the session being disposed at the end, prohibiting further iterative interactions. You can think of stateless as treating an engine like a function call with optional return results.

The foundation for this is the CommandExecutor interface, which both the stateful and stateless interfaces extend.

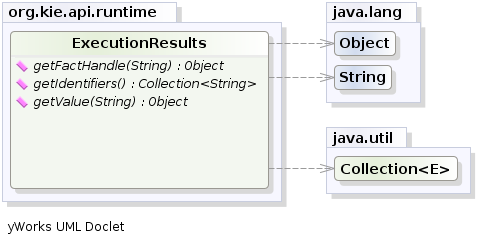

This returns an ExecutionResults:

The CommandExecutor allows for commands to be executed on those sessions, the only difference being that the StatelessKieSession executes fireAllRules() at the end before disposing the session.

The commands can be created using the CommandExecutor .The Javadocs provide the full list of the allowed comands using the CommandExecutor.

setGlobal and getGlobal are two commands relevant to both Drools and jBPM.

Set Global calls setGlobal underneath.

The optional boolean indicates whether the command should return the global’s value as part of the ExecutionResults.

If true it uses the same name as the global name.

A String can be used instead of the boolean, if an alternative name is desired.

StatelessKieSession ksession = kbase.newStatelessKieSession();

ExecutionResults bresults =

ksession.execute( CommandFactory.newSetGlobal( "stilton", new Cheese( "stilton" ), true);

Cheese stilton = bresults.getValue( "stilton" );Allows an existing global to be returned. The second optional String argument allows for an alternative return name.

StatelessKieSession ksession = kbase.newStatelessKieSession();

ExecutionResults bresults =

ksession.execute( CommandFactory.getGlobal( "stilton" );

Cheese stilton = bresults.getValue( "stilton" );All the above examples execute single commands.

The BatchExecution represents a composite command, created from a list of commands.

It will iterate over the list and execute each command in turn.

This means you can insert some objects, start a process, call fireAllRules and execute a query, all in a single execute(…) call, which is quite powerful.

The StatelessKieSession will execute fireAllRules() automatically at the end.

However the keen-eyed reader probably has already noticed the FireAllRules command and wondered how that works with a StatelessKieSession.

The FireAllRules command is allowed, and using it will disable the automatic execution at the end; think of using it as a sort of manual override function.

Any command, in the batch, that has an out identifier set will add its results to the returned ExecutionResults instance.

Let’s look at a simple example to see how this works.

The example presented includes command from the Drools and jBPM, for the sake of illustration.

They are covered in more detail in the Drool and jBPM specific sections.

StatelessKieSession ksession = kbase.newStatelessKieSession();

List cmds = new ArrayList();

cmds.add( CommandFactory.newInsertObject( new Cheese( "stilton", 1), "stilton") );

cmds.add( CommandFactory.newStartProcess( "process cheeses" ) );

cmds.add( CommandFactory.newQuery( "cheeses" ) );

ExecutionResults bresults = ksession.execute( CommandFactory.newBatchExecution( cmds ) );

Cheese stilton = ( Cheese ) bresults.getValue( "stilton" );

QueryResults qresults = ( QueryResults ) bresults.getValue( "cheeses" );In the above example multiple commands are executed, two of which populate the ExecutionResults.

The query command defaults to use the same identifier as the query name, but it can also be mapped to a different identifier.

All commands support XML and jSON marshalling using XStream, as well as JAXB marshalling. This is covered in Drools commands.

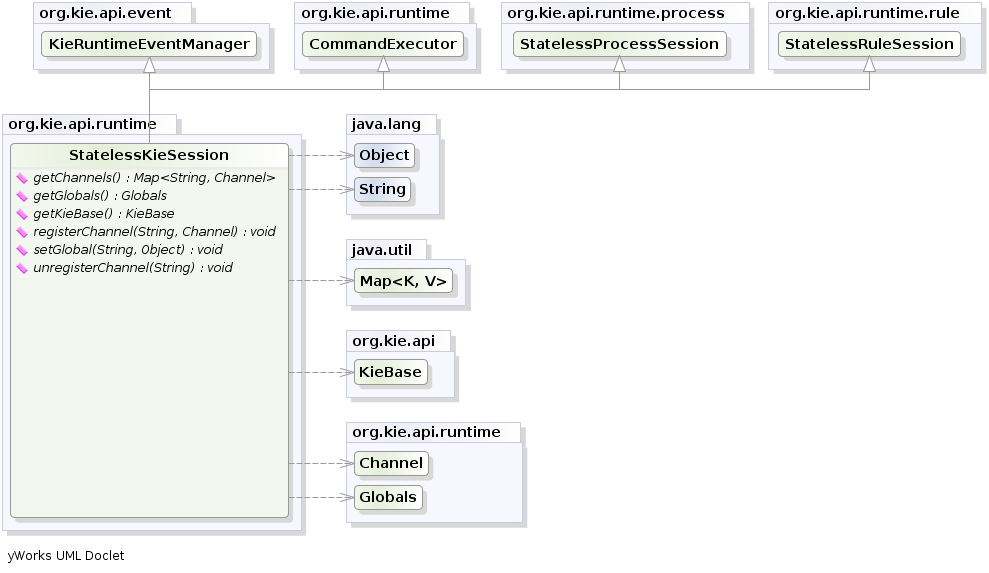

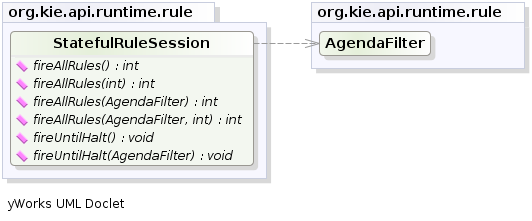

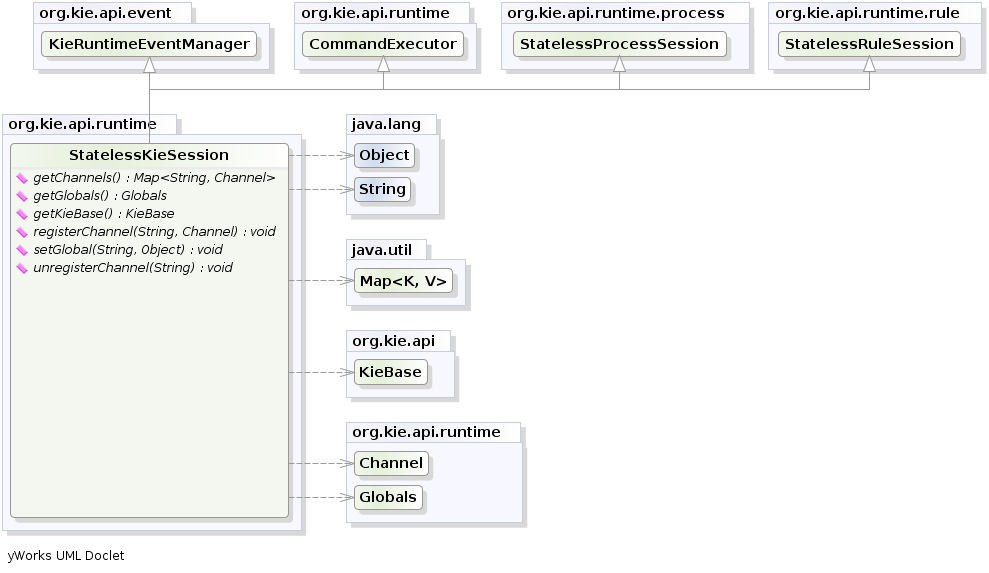

2.2.4.7. StatelessKieSession

The StatelessKieSession wraps the KieSession, instead of extending it.

Its main focus is on the decision service type scenarios.

It avoids the need to call dispose().